IADS Exclusive Articles

IADS Exclusive – Territory expansion: The new playbook for cultural relevance in retail

IADS Exclusive – Territory expansion: The new playbook for cultural relevance in retail

Brands are no longer confined to their original product categories. Instead, they are increasingly expanding their reach into new brand territories, ranging from additional product categories to sports, culture, and entertainment, redefining not just what they sell, but what they represent. This diversification is not about opportunistic line extensions. It’s a calculated repositioning aimed at opening new revenue streams, for sure, but also deepening consumer engagement and embedding brands into broader lifestyle ecosystems. Whether through launching cosmetic lines, furnishing homes, associating with sports performances, staging cultural experiences or producing films, brands are reimagining their roles in consumers’ lives, moving from product providers to curators of aspirational living.

From that perspective, Louis Vuitton, a critical brand for any luxury department store, is probably the most striking example, ticking all the boxes of a brand that has transformed into a lifestyle ecosystem. While many other brands are expanding their territory, department stores need to adapt to welcome these new brand expressions.

Lipstick logic: When brands turn to beauty

The most usual way to expand brand territory is to venture into new product categories. At a time when the beauty and wellness industry has been booming, brands have recently ventured into the coloured cosmetics category. Hermès is a significant example in the luxury price bracket. While they first launched fragrances in 1950, the Perfume & Beauty ‘only’ represented 3.5% of the brand’s total revenue in 2024 (in comparison, Chanel’s beauty business is estimated to represent 35% of the total revenue in 2024). It took Hermès 70 years to initiate a careful foray into colour cosmetics in early 2020 during Covid, with disappointing results. Since then, the Perfume & Beauty division has built up, doubling from €263 million in 2020 to €535 million in 2024, growing 9.3% YoY. While it’s a very significant achievement, it represents limited growth compared to the rest of the business. In 2024, Hermès achieved a consolidated revenue of €15.2 billion, marking a 14.7% increase over the previous year.

On its side, Louis Vuitton began by relaunching its perfume division in 2016. This initiative marked a return to the brand’s historical roots, as Louis Vuitton had released its first perfume in 1927, though it was quickly discontinued. After fragrances, Louis Vuitton will debut colour cosmetics in fall 2025 with the British makeup artist Dame Pat McGrath as its creative director. The line, which will be called La Beauté Louis Vuitton, is the fashion house’s first foray into cosmetics since the 1920s, when it offered a range of powder compacts, brushes and mirrors.

The market is crowded with prestige and luxury brand new beauty lines: Prada, Celine, Rabanne and Dries Van Noten have all debuted cosmetics in the past years. But not only does luxury follow this trend. In 2023, Ecoalf’s founder, Javier Goyeneche (a guest speaker at one of the recent IADS CEO meetings), expanded into sustainable beauty products, seeking to bring its environmental ethos to everyday personal care with Ecoalf Wellness. Assuming customers would be seduced by the brand’s circular principles applied to skincare and hygiene, the brand eliminates single-use plastics and drastically reduces water-heavy formulations, delivering powder-based shampoos, deodorants, and more enclosed in reusable aluminium containers that can last over twenty years.

Not all ventures are successful, though. In 2019, Birkenstock launched a skincare line including eye cream, anti-wrinkle cream and more. While Birkenstock’s surprising move into the beauty sector could represent a natural yet bold progression from its DNA of wellbeing to a broader vision of self-care, these products didn’t sell because offering products such as eye cream was probably too far-fetched. Closer to its DNA and core business, Birkenstock ventured again into beauty in 2024 with Care Essentials, a short and focused foot care line that aligns more closely with the brand ethos. Overall, this transformation highlights a broader trend in which heritage labels utilise their domain expertise to expand into adjacent lifestyle categories, hoping to deepen consumer engagement and open new revenue streams.

Living the brand: How fashion brands furnish everyday life

Brands are not only venturing into beauty but also embracing home design. The first brand to truly venture into furniture, lighting, and home accessories is Armani, which introduced the Armani/Casa label in 2000. This strategy to integrate domestic life continues with the Louis Vuitton Objets Nomades collection, introduced in 2012. Initially conceived as a series of travel-inspired furniture pieces, the collection has since evolved into a substantial home design portfolio, featuring collaborations with recognised designers such as Patricia Urquiola, India Mahdavi, and the Campana Brothers. These limited-edition objects are presented as collectables, elevating Louis Vuitton from a fashion house to a purveyor of high-art domestic experience.

Fast fashion brands also account for successful forays in the home categories. Zara, H&M, and more recently Primark have each undertaken significant strategic expansions into home products to capture a rapidly growing homeware market shaped by post-pandemic lifestyles. Starting in 2003, Zara Home leveraged the same fashion calendar and just‑in‑time logistics that made apparel successful, but uses relatively low discounting compared to apparel, maintaining a premium feel. Financially, the division has matured into a significant revenue driver, with 2018 figures reaching approximately €830 million out of the €16.62 billion total revenue.

H&M adopted a similar but later strategy, first entering the home arena in 2008. Initially sold online and later in stores, the business rationale for H&M Home followed a clear logic: leverage a trusted mass-market retail infrastructure to capture lifestyle spend while maintaining price accessibility, mirroring its “fashion for the many” ethos. In doing so, H&M strengthened its omnichannel ecosystem, using home products to increase basket size and frequency of visits.

Finally, Primark’s entrance into homeware has taken a different trajectory, rooted in physical retail dominance. The retailer began testing its homeware range alongside clothing before making a decisive strategic shift in 2025. The retailer opened its first dedicated Primark Home store in Belfast, showcasing small furniture, bedding, ceramics, and travel essentials in a standalone environment.

Temporary territories: When department stores catch the zeitgeist

There is also an agile way to catch customers’ attention and a share of their wallets. Selfridges and Le Bon Marché offer vivid examples of how department stores have opportunistically tapped into lifestyle trends by temporarily expanding their product ranges to capture additional revenue streams. Following Covid, Selfridges identified an unexpected yet powerful consumer behaviour toward nature, gardening and wellbeing. By mid-2021, its London, Manchester, and Birmingham stores had introduced pop-up garden centres offering a variety of plants and tools, compost, and related apparel. The effort helped Selfridges capture a surge in “green-fingered” spending, translating consumer leisure budgets into in-store impulse purchases on plants and horticultural expert consultations. While Le Bon Marché had the same initiative, this pivot exemplifies how a temporary trend can be monetised through short-term, high-impact product ventures. These initiatives were also incredibly smart in attracting more local consumers, especially at a time when tourism was halted.

Le Bon Marché took an agile approach to pet products in early 2025 by transforming its permanent pop-up spaces into a canine playground under the exhibition banner “Je t’aime comme un chien!”. The initiative mixed dog-centric products, from designer collars, bowls, bespoke toys, treats, spa and grooming services, to a café, workshops, personalisation and photo booths, with immersive visual installations such as big prop bones throughout the store. This thematic takeover capitalised on a widely observed surge in pet spending. Generating high traffic and engagement, Le Bon Marché found the right way to bring dogs and their owners into the shopping journey, strategically steering discretionary spending toward products that align with a momentary yet powerful cultural obsession.

These initiatives are less about permanent transformation and more about momentary alchemy. Selfridges’ plant pop-ups and Le Bon Marché’s dog-themed extravaganza both illustrate a modern department store strategy: not just selling things, but staging culturally resonant experiences that trigger new purchasing behaviours. By reading the zeitgeist and moving fast, with highly curated inventory and thematic environments, these stores created agile revenue plays that capitalised on emergent consumer trends at just the right moment.

Gold, speed, and symbolism: Luxury meets global sports events

Brands venturing into sports is nothing new. Yet Louis Vuitton’s involvement in Formula 1 and the 2024 Olympic Games reflects an increasingly assertive strategy to position the brand at the centre of contemporary cultural spectacle. Over the last decade, Louis Vuitton has steadily moved into the realm of global prestige events, not as a traditional sponsor, but as a supplier of symbolism. In 2021, the brand unveiled a bespoke monogrammed trophy trunk for the Formula 1 World Championship. Its repeated presence on the podium reinforced the brand’s authority and symbol of positive rituals and victory. The move into Formula 1 coincided with a generational shift in the sport’s audience, the sport’s blending of technology, drama, and internationalism offering the brand a stage that mirrored its own values: precision, control, spectacle, and heritage. In early 2025, Louis Vuitton announced a new 10-year significant partnership with Formula 1, beginning with the title sponsorship of the March 2025 Australian Grand Prix. This initiative capitalises on Formula 1’s growing popularity, which attracted six million race attendees and 1.5 billion TV viewers last year, with particularly strong growth among women and youth demographics. The partnership will enable Louis Vuitton to offer unique hospitality experiences for top clients while reaching new audiences. It’s a compelling example of the brand’s broader transformation from a traditional luxury retailer to a cultural powerhouse.

But Louis Vuitton’s ambitions in the sports ecosystem are not isolated. In 2024, the brand expanded its reach further by becoming an official partner of the Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games, joining LVMH’s broader role as a premium sponsor of the event. As part of this engagement, Louis Vuitton designed and produced custom-made trunks for the Games medals. Similar to Formula 1, this foray signals a brand strategy anchored in recruiting new middle-class consumers. In both cases, the brand builds the physical artefacts through which these moments are staged. By embedding itself within the most visible and emotionally charged moments in sport, Louis Vuitton has redefined the boundaries of luxury participation. No longer solely anchored to the runway or its store network, the brand now lives elsewhere, and (already) everywhere.

Beyond commerce: Art as identity

Over the past three decades, luxury groups have moved far beyond fashion and retail to establish a lasting presence in contemporary art and culture. Similar to sports, this shift is not simply an act of sponsoring but a repositioning of luxury as a global cultural force. LVMH, Kering, and Richemont have each established cultural ecosystems to give their brands artistic legitimacy. For LVMH, this began with the 1990 creation of the Prix LVMH des Jeunes Créateurs, followed by the launch of the Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2014, which has become a cultural landmark in Paris. The Fondation has hosted major exhibitions drawing over a million visitors annually and positioning LVMH not just as a backer of the arts, but as a producer of major cultural events on par with the world’s leading institutions.

On its side, the Pinault Collection, distinct from the Kering group, represents one of the most ambitious private interventions in the contemporary art world. Long before the 2021 opening of the Bourse de Commerce in Paris, Pinault had already established two major cultural outposts in Venice, marking a sustained engagement with art. The Bourse de Commerce not only embodies a private collector’s vision but also illustrates how the resources of the luxury sector can be redirected to create enduring cultural institutions that have a lasting impact far beyond fashion.

Richemont has taken a more classical route, yet no less ambitious. The Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, established in 1984, predates most other luxury group initiatives and stands out for its consistent, long-term engagement with artists across disciplines. Located in Paris, it recently announced plans to move to a larger site near the Louvre, underlining its institutional ambitions.

The logic here is not transactional but foundational: art and culture are not marketing vehicles but narrative extensions of what luxury is presumed to be: timeless, intellectual, emotional, and transformative. In embedding themselves into art, luxury groups are not just financing creativity, they are quietly recasting themselves as cultural institutions in their own right. This repositioning elevates their brands beyond fashion cycles, resonating long after a runway show ends.

Fashion cinematic turn: there’s no business like show business

As the boundaries between fashion and entertainment continue to dissolve, a growing number of luxury houses are entering the film industry not as sponsors or costume collaborators, but as producers and curators. Louis Vuitton, Saint Laurent, and AMI Paris have each taken distinct yet strategically aligned steps into the film industry, using cinema as both a storytelling device and a cultural amplifier. In 2023, Louis Vuitton launched 22 Montaigne Entertainment, a dedicated production entity. Unlike earlier iterations of fashion-film collaborations, which often blurred into extended commercials, 22 Montaigne Entertainment aims to finance and develop projects. In partnership with Superconnector Studios, this division will be responsible for identifying opportunities for LVMH brands to collaborate with entertainment entities to co-develop and co-produce entertainment properties across film, television, and audio. However, it is likely that LVMH also has an eye toward producing larger, more mass-entertainment offerings, such as The House of Gucci movie, which grossed $166 million worldwide at the box office.

Saint Laurent, by contrast, has made the most direct and structurally ambitious move into filmmaking. In 2023, the house launched Saint Laurent Productions, becoming the first luxury brand to create a registered film production company. Its debut collaborations with auteurs such as Pedro Almodóvar and David Cronenberg made immediate headlines at major festivals including Cannes and Venice. Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Perez movie was a particularly striking example: it co-produced the entire feature, collaborating closely with the other movie-producing companies. The result is not mere branding, but active, creative authorship, with Anthony Vaccarello, Saint Laurent’s creative director, serving as a credited producer on the project.

AMI Paris’s entrance into the cinematic world took a more institutional turn in 2024 with the creation of the Grand Prix AMI Paris de la Semaine de la Critique, an award presented during the Cannes Film Festival that celebrates emerging filmmakers. Founded by AMI Paris’s founder and creative director Alexandre Mattiussi, the prize is designed to support the kind of filmmaking that aligns with AMI’s cultural positioning.

Together, these three brands represent different yet converging models for how fashion intersects with cinema. Louis Vuitton approaches it as a narrative architecture surrounding the brand’s universe, Saint Laurent treats it as a parallel industry in which to operate and AMI Paris uses it to enhance the brand’s emotional temperature. Each strategy points to the same conclusion. In a saturated visual economy, luxury no longer communicates through clothing alone. With its emotional depth, films offer a medium through which to project identity, build mythology.

As brands move beyond their traditional domains, a clear ambition emerges: catching all consumer life moments. Louis Vuitton’s ventures outside of its traditional categories are more than secondary revenue streams. They are expressions of the brand’s DNA and values, only reinforcing its position as a global cultural arbiter. Collectively, these moves signal a profound shift in the role of brands, from product makers to global cultural forces. In extending their territory, brands are not just chasing growth, they are shaping the consumers’ lives, raising questions about their cultural and emotional dominance.

For department stores, these new brand territories certainly require adaptation, but they also represent unprecedented opportunities to attract new consumer groups, making stores more exciting and livelier. Boring retail is, more than ever, dead!

Credits: IADS (Christine Montard)

IADS Exclusive – Retail’s new front door: How hospitality becomes core business

IADS Exclusive – Retail’s new front door: How hospitality becomes core business

Over the past three decades, hospitality, whether in the form of restaurants, bars, cafés, or hotels, has evolved from a brand-building side project into a strategic pillar for non-hospitality brands across various sectors. What began as bold experiments by luxury fashion houses has transformed into a multi-industry movement, as companies seek to deepen emotional engagement, increase traffic and customer dwell time, and unlock new revenue streams. Hospitality now serves as a customer acquisition tool and can transform into a profit centre. As the lines between retail, lifestyle and experience continue to blur, hospitality has evolved not just as a trend but as a long-term strategy, one that requires brands to demonstrate creativity and operational excellence.

Hospitality has been an integral part of the department store business since its inception. Almost two centuries after Le Bon Marché opens a reading room free of charge to husbands waiting for their wives, department stores up the hospitality ante to better serve customers and compete with their brand partners’ own hospitality engines.

No longer a vanity sideline, hospitality is becoming the front door to brand ecosystems and a credible profit driver. Department stores that curate these experiences can turn lattes, food and maybe room keys into the next generation of retail loyalty.

A selective 30-year history of hospitality at non-hospitality brands

Luxury fashion at the forefront…

Hospitality ventures by non-hospitality brands began in 1998 with a luxury brand. Giorgio Armani unveiled plans for the first hotel, an idea realised in Dubai and Milan a decade later and widely viewed as the proof-of-concept for luxury fashion hospitality. The following year, Ralph Lauren opened RL Restaurant in Chicago, showing that restaurants could amplify a lifestyle label’s aura without leaving its home market. The early 2000s marked the first wave of upscale experiments: Versace debuted Palazzo Versace in Australia in 2000 and in Dubai in 2016. In 2004, Bulgari launched its Milan hotel. Soon enough, non-luxury brands entered the hospitality game.

Luxury fashion’s second wave occurred between 2014 and 2020. In 2014, Prada took an 80% stake in Milanese pasticceria Marchesi 1824. Dior launched Café Dior in Seoul in 2015, Fendi installed Zuma on its rooftop in Rome in 2016, and Gucci Osteria earned a Michelin star two years after opening in 2018. In the 2020s, the movement matured into scale plays and mixed-use flagships. While planning a hotel to open on Paris’ Champs-Élysées in 2026, Louis Vuitton opened its first in-store Le Café V in Osaka in 2020 and Paris in 2022, as part of the LV Dream exhibition. That same year, Dior Paris’ Avenue Montaigne flagship store reopened, flanked by a café and a restaurant by renowned French chef Jean Imbert. Exploring other hospitality options, Louis Vuitton then opened a lounge on top of its Doha airport store in 2023. The space includes designer furniture pieces, as well as a 3-star Michelin restaurant.

… Followed by other industries…

By the mid-2000s, other industries had joined in, including the automotive, beauty and banking sectors: BMW introduced fine dining at Munich’s BMW Welt in 2007. The momentum accelerated in the 2010s with a second wave of ventures. With six different restaurants, Ferrari World in Abu Dhabi (2010) proved that theme-park F&B could drive sales, while beauty label L’Occitane combined cafés and spas from 2011 onward. Financial services moved next: Capital One Cafés debuted in 2012, and American Express rolled out its Centurion Lounges in 2013. In 2016, Samsung opened its NYC flagship store, including a Stand Coffee.

… And premium and mass retail

In 2001, French lingerie brand Etam opened a now-closed 4,000 sqm flagship store in the former Samaritaine Sport building, featuring a restaurant supervised by renowned chef Alain Ducasse. Urban Outfitters’ first Terrain garden café launched in 2008. The first Muji hotel opened in 2018, followed by Maisons du Monde (which opened two hotels in 2019, in Nantes, and 2021, in Marseille) and IKEA (in Grand Canaria in 2025). In 2023, Tokyo saw the first Maison Kitsuné café. That same year, Zara opened its first café in Dubai’s Mall of the Emirates, refining the concept through 2024 with the opening of Zacaffé in Madrid, part of its premiumisation strategy.

This concise three-decade history highlights brands’ expanding ambitions—from single-brand one-time initiatives to global, data-driven ecosystems that boost customer lifetime value, foster loyalty, and deliver EBITDA margins sometimes exceeding those of their core product lines.

Between halo and headwinds: hospitality’s retail reality

Beyond the buzz: when hospitality fails

Hospitality is not a perfect world. On top of potential rising operating costs and economic downturns that refocus customers on commodities, several risks are attached to hospitality:

- Concept and customer fatigue: for example, Lexus restaurant in New York’s Meatpacking District shut permanently in January 2022 after struggling to fill seats outside the launch buzz. This shows that even a best-in-class collaboration (with Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group) cannot offset footfall gaps if the brand story isn’t locally resonant. This also highlights the potential struggle of partnering with a different industry.

- Brand-licence fracture: Versace walked away from its 15-year branding deal on Australia’s Palazzo Versace. The resort was renamed Imperial Hotel in 2023. Even with the right partner, licence renewals can hinge on one side’s changing strategy.

- Market oversaturation: when you’re not Starbucks, how many lattes can a brand sell? Rapid café rollouts can dilute exclusivity. South Korea’s coffee shop count fell for the first time in decades, down 743 outlets YoY in Q1 2025, making it more difficult for brands to find their way in the hospitality business.

- Brand dilution: a mediocre execution can undermine the halo effect brands seek. Additionally, even successful brands in the hospitality business face challenges. Maison Kitsuné, for example, has opened 25 Café Kitsuné, which represent around 10% of the company’s turnover. While they have played an essential role in the growth and development of brand awareness, cafés are now somehow more successful than the RTW products.

From dwell time to data: hospitality as a retail growth engine

Hospitality can help non-hospitality brands exploit under-served white spaces in the customer journey (such as banking wait time or car showroom friction). For fashion retailers, hospitality touchpoints can nurture loyalty and transform into high-frequency visits between low-frequency purchases, such as those between 18 to 24-month handbag purchases. Moreover, hospitality can lead to increased customer spending. Harrods’ director of restaurants and kitchens mentioned in 2023 that they had “almost 10,000 bookings made for the Dior café in the first four days of opening. If we take the Gen Z customer, they are telling us they want to spend their money on luxury, fashion, and dining. This combination is gold.” The restaurant and café business is also a data goldmine, providing retailers with new customers and additional information, such as dietary preferences, that can feed CRM personalisation engines. Customer acquisition costs are also unrivalled compared to digital ads, as a €5 café voucher can result in new customer data and future conversion.

In the case of IKEA, restaurants represent a sophisticated retail strategy that leverages food at break-even or slight loss to drive traffic, increase dwell time, and ultimately boost sales. IKEA is essentially subsidising food costs to generate higher-margin furniture sales. Restaurants extend store visits and increase impulse purchases. The traditional shopping journey, “browse → select → purchase”, transforms into an enhanced model: “dine → browse → rest → browse → purchase → maybe dine again.” IKEA restaurants have a strategic psychological impact, too. In a somewhat overwhelming shopping environment, they reduce shopping fatigue through strategic breaks, create positive associations with the brand and transform utilitarian shopping into a leisure experience1.

Overall, brands can leverage hospitality to extend lifestyle narratives, capture higher dwell times, generate significant turnover, and build high-margin revenue streams, as restaurants can achieve approximately a 23% EBITDA, significantly above core RTW margins.

Temporary, tactile, tactical: the rise of ephemeral hospitality

A coherent hospitality concept should make the intangible brand universe sensory: scent, music, menu curation and service rituals translate logos into lived experiences. While many brands have turned this ambition into a series of café openings, how to differentiate from the crowd? Onitsuka Tiger succeeded in that mission on the occasion of their red concept opening in London’s Covent Garden in Spring 2025. Instead of opening a permanent in-store café, the brand decided to partner with a local pub, the neighbourhood staple Crown & Anchor, blending a Japanese night feeling and a British pub atmosphere. The pub was transformed for a limited time into the “Onitsuka Tiger Tavern”. The classic British watering hole was reimagined through a Tokyo nightlife lens, completed with heritage posters and a karaoke session. The usual wood-panelled pub interior was given a crimson red Onitsuka twist. Bartenders served Japanese Suntory whiskey, Wagyu tartare plates, and a Japanese take on traditional fish and chips. Instead of a permanent café, the Onitsuka Tiger Tavern will resume only for significant moments such as brand events or product launches. Communication will go through the brand’s Instagram account. Not only does it allow the brand to blend into the local environment and community, but it also avoids heavy investments in CAPEX and staff as well as potential customer fatigue.

Similarly, to better anchor itself in Paris, the Italian brand Pucci partnered with a laid-back institution in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Bar de la Croix Rouge. The café’s awnings and terrace are adorned with one of the iconic, colourful prints until the end of July 2025. A one-night-only aperitivo hosted local celebrities and friends of the house, mixing Italian and Parisian flair.

Another interesting and unprecedented hospitality offspring initiative comes from IKEA. During July 2025, they opened their ‘Billy-othèque’ (a pun mixing Billy, the name of the iconic bookcase, and the French word for bookcase) in Paris. On the Seine bank in front of Paris’ biggest library and shrewdly positioned just 15 minutes away from their latest Paris store, a 30-metre-long open-air Billy bookcase displayed thousands of books of any kind with a simple idea based on sharing and community-building: participants gave out a book they love and left with another book that has caught their attention. Reading advisors were available to assist the public in selecting their books. Readings for the younger generation were organised every day at 4.30 pm. This initiative demonstrates how alternative hospitality formats are evolving and becoming increasingly relevant in terms of standing out from the crowd.

How hospitality reinvents department stores

Gastronomy and gross margin: when retail goes gourmet

One of the oldest examples of a retailer embracing in-store dining is the Walnut Room, which dates back to 1907 at Macy’s in Chicago. Now integral to any elevated retail experience, food offerings, and especially fine dining, have become a department store staple. The past few years have seen some interesting ventures. In 2022, El Corte Inglés became the first department store in the world to get a Michelin star for its RavioXO restaurant, opened at its Castellana store with renowned Spanish chef Dabiz Muñoz. The collaboration with El Corte Inglés continued with the opening of a second restaurant, located in the Serrano store, a few months later.

Hospitality feeds cross-selling models. Research by Harrods showed that when customers engage with their 26 restaurants and bars, they spend twice as long in the building and twice as much money. Additionally, when the Prada Caffè opened at Harrods in London in April 2023, a viral TikTok reel showcasing the cafe recorded 220,000 views within the first 24 hours of its posting, generating brand awareness and attracting customers in-store. In NYC, Printemps Wall Street’s recently opened store follows a similar strategy and dedicates a third of the space to F&B offerings. They have appointed renowned Haitian chef Gregory Gourdet as their culinary director, who has created five distinct concepts for the store, including an all-day casual café, a classic Parisian-inspired raw bar, and more. However, the most critical F&B option is undoubtedly the Maison Passerelle restaurant. It aims for a Michelin star and is considered one of the 10 most important restaurant openings in NYC in 2025.

In Summer 2025, Galeries Lafayette established an unprecedented partnership with Air France, transforming its rooftop into an aeroplane-themed dining destination, featuring Business Class menus created by three-star chef Régis Marcon and World’s Best Pastry Chef Nina Métayer. The restaurant, accommodating 20 covers both indoors and outdoors with two lunch services daily, recreated the intimate atmosphere of Air France’s airport lounges while offering panoramic views of Paris. The Air France rooftop restaurant builds upon a series of successful dining experiences. In September 2024, as it celebrated its 130th anniversary, Galeries Lafayette showcased its expertise in culinary ventures with an exclusive dining event under its iconic dome, setting a precedent for innovative food partnerships.

From retail to lodging: hotels as the ultimate brand touchpoint

Whether it’s Armani or Bulgari, luxury brands have been pioneers in opening hotels. Lately, building on its Art of Travel DNA, Louis Vuitton is adding full lodging to its now-usual “shopping + café” model. 103-111 avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris will become a hotel again2. The 25,000 sqm block sits a door’s distance from Louis Vuitton’s current flagship at 101 avenue des Champs-Élysées. This will enable the luxury giant to open a mixed-use complex featuring an enlarged Louis Vuitton megastore on the lower floors and a luxury hotel spanning approximately 6,000 sqm. Every square metre will then become a loyalty touchpoint. If Paris succeeds, it could serve as a blueprint for further openings.

There is room and interest for department stores also to enter the hotel business, as profitability doesn’t compare, especially at a time when traditional retail is under pressure and customers are looking for experiences over shopping. FY 2024 adjusted EBITDA as a percentage of total revenue is around 29% for Host Hotels & Resorts (the largest U.S. lodging company), 30% at Hilton, and only around 8% at Macy’s Inc. Selfridges considers venturing in the hotel business. The dormant Old Selfridges Hotel occupies the block at 1 Orchard Street and 40 Duke Street, directly behind the Selfridges store on Oxford Street. The 294-key hotel shuttered in 2008 and has since been stripped back to a concrete shell used for fashion-week shows and art pop-ups. When Central Group and Signa bought Selfridges for £4 billion in December 2021, they announced that reactivating the hotel was the deal’s “significant value-upside” lever. There has not been any update on the project to date. In any case, hospitality can be an option for unused real estate and leverage new potential, as is the case with LVMH using a part of the Samaritaine store for a 5-star Cheval Blanc hotel.

Beyond VICs: when hospitality becomes a status strategy

Hospitality in department stores reached a new peak in June 2025 when Selfridges announced it would transform its 4th-floor executive offices into a members-only destination, marking a significant evolution in its customer engagement strategy. Named 40 Duke, the private club will feature an internal bar and lounge accommodating 80 covers, a private dining room and terrace with 14 covers, and an external dining terrace seating 50 people. Operating hours will extend from 8:00 am to 12:30 am, Sunday to Thursday, and until 1:30 am on Friday and Saturday, with the terrace available from 9:00 am to 11:00 pm daily. This strategic transformation of office space into a premium members’ venue reflects the broader luxury retail trend of creating exclusive experiences for high-value customers turned members, while maximising property utilisation in prime locations. Building on that perspective, IADS members could build a luxury department store network to offer hospitality membership perks to travelling VICs.

As it gives a renewed purpose to physical stores, hospitality is no longer an accessory but the new retail battleground for loyalty. The past thirty years illustrate a shift from one-off showcases to data-driven ecosystems that extend the brand narrative and drive additional business. Yet not every venture succeeds: brand dilution, oversaturation, and poor execution remain constant risks. The future belongs to retailers who can design resonant concepts that add meaning, not just margin. Whether through immersive restaurants, temporary cultural takeovers or full-scale hotels, brands that turn hospitality into a genuine extension of their identity will be best placed to capture customer loyalty and lifetime value.

Enhanced lifestyle credentials, elevated perceived value and brand equity, increased customer engagement and dwell time, and a way to differentiate from competitors. Although the ROI may not be immediately quantifiable, the impact of these hospitality-inspired experiences is a strategic investment for future retail success. For customers, it offers the convenience of multiple services under one roof, the experiences they crave, and entertainment and engagement beyond shopping.

Credits: IADS (Christine Montard)

IADS Exclusive: From orchestration to reinvention, how omnichannel mature

IADS Exclusive: From orchestration to reinvention, how omnichannel mature

Retailers have spent the last decade chasing the promise of omnichannel, often equating it with being everywhere at once. But the real challenge today is not ubiquity—it is focus. The most advanced players are learning to guide customers toward journeys that create value, while reshaping their store networks into engines of proximity, trust, and fulfilment. Omnichannel is no longer just about touchpoints; it is about rethinking the very infrastructure of retail.

The IADS has published several articles on the topic, including from Dr Christopher Knee, the Association’s honorary advisor. To go further and make conceptual advances, we invited Robert Rooderkerk, an Associate Professor at Erasmus University (Rotterdam), to give IADS CEOs an idea of where research about Omnichannel stood at the time. By a fortunate coincidence, his lecture took place the very week when he published his latest article in the Harvard Business Review, When omnichannel retailers don’t deliver what customers ordered.

Rooderkerk holds an M.Sc. in Econometrics with a specialisation in logistics from Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Ph.D. in Marketing from Tilburg University – both earned with cum laude distinction. His research focuses on the intersection of marketing and operations, addressing critical challenges in omnichannel retail and retail analytics.

Drawing from collaborative academic research, insights from management journals and popular media, and conversations with practitioners across industries such as apparel, consumer electronics, grocery retail, and DIY— he offered a fresh view on the steps department stores could take to become truly omnichannel and remain competitive against specialist retailers and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) brands.

Introduction: the new competitive reality in omnichannel retail

Today, department stores face competition from many directions. Digitally native brands are opening their own flagship stores to protect their brand and collect richer customer data. Specialists like Sephora are winning by offering very deep product ranges and seamless cross-channel experiences. At the same time, luxury online marketplaces are setting new standards for what customers expect.

In this context, department stores can’t just keep up with omnichannel capabilities—they need to use those tools to guide customer behaviour. In other words, they must stop relying only on defensive strategies and instead take an active role in shaping customer experiences that increase profitability. To achieve this, Rooderkerk suggests two angles.

The first one is to push omnichannel optimisation forward: the goal of omnichannel is no longer just connecting all channels but actually optimising them—steering customers toward the paths that are most valuable for the retailer. This can mean higher profitability, better efficiency, or progress toward sustainability. To make this work, retailers need a more precise understanding of how customers move between channels and touchpoints. The most advanced companies have gone past simply allowing every possible shopping journey. Instead, they now nudge customers to channels or combinations of channels that bring higher margins, reduce returns, or balance inventory across the network. They use data to shape behaviour through personalised offers, dynamic user experiences, and fulfilment strategies that serve business goals.

The second one is to make store networks work through smaller formats. Smaller formats are becoming strategic assets: lower cost, highly flexible nodes for last mile, localised assortments, and experiential service—especially in cities. Rooderkerk insists that store strategy and digital strategy can no longer be separated. Each store should not only be judged on sales per square metre but also on how it supports customer experience, delivery efficiency, and brand visibility across all channels.

The omnichannel evolution: moving into the optimisation stage

The term “omnichannel” is often misunderstood—if not outright misleading. Robert Rooderkerk emphasises that omnichannel is not about being present in every possible place at once, but about being present where it matters, delivering value to both the customer and the business simultaneously. This shift in perspective is essential.

According to Rooderkerk, the industry’s fixation on perfectly seamless customer journeys has pushed many companies into strategies that don’t make money. Removing every bit of friction can look customer-first, but if there’s no solid business reason, it becomes financially unsustainable. The goal isn’t to abolish all friction—it’s to remove friction intelligently where it supports broader strategic objectives. In this sense, omnichannel isn’t a tech spend or a tactical add-on—it’s a mindset—a mindset of continuous evolution, iteration, and optimisation.

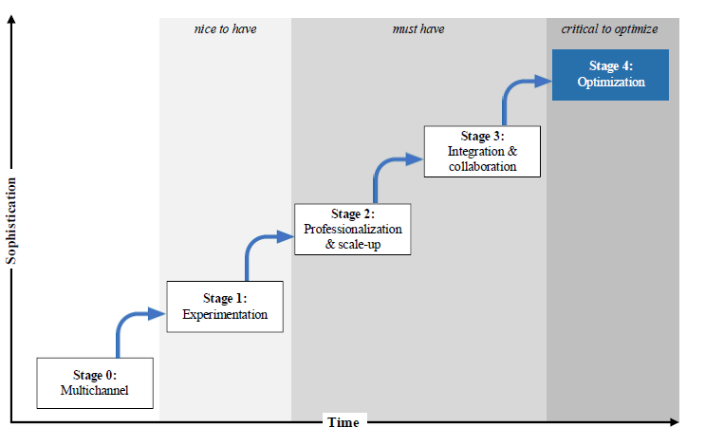

Through a broad research effort with C-minus-one level leaders (such as heads of omnichannel, operations, and marketing) across categories from luxury to consumer electronics, in 2025, Rooderkerk outlined a maturity model that most companies are currently moving through.

Credits: Robert Rooderkerk, 2025

The journey typically begins in a fragmented, multichannel phase, where online and offline channels are siloed and serve different customer segments. This setup fell short during the COVID-19 pandemic, when retailers rushed to stand up click-and-collect using a mix of manual workarounds and disconnected systems. That time was the “experimentation” phase: it worked, but it wasn’t efficient.

As retailers progressed, they moved into what Rooderkerk calls the “ramping up” stage—scaling services like same-day or even same-hour click-and-collect, expanding geographic reach, and increasing speed. Still, most companies today are stuck in this phase or the next, known as “channel integration.”

This third stage focuses on omnichannel order orchestration—using centralised systems to choose the best fulfilment nodes, whether stores or distribution centres, based on stock availability, distance, and delivery efficiency. Yet many organisations are still held back by internal silos between digital and physical teams, with ongoing “tribal” conflicts over budgets, authority, and strategy.

The move from a channel-led to a customer-led organisation is signalled by customer journey segmentation. That means spotting and investing in the most valuable or frequent journeys based on transaction volume or customer value. Instead of trying to optimise every possible journey, the most forward-looking retailers focus on the ones with the most significant return potential.

But the most advanced retailers don’t just support these journeys, they shape them. This higher level of maturity, which Rooderkerk calls “omnichannel optimisation,” is about steering customers toward the channels and touchpoints that improve profitability or customer equity. Strategic guidance might mean encouraging in-store visits in areas where delivery performance is weak, or nudging customers away from home delivery when in-store interactions offer better upsell opportunities or long-term loyalty benefits.

Holland & Barrett, for example, uses different nudges by market to influence channel selection. In the UK, customers are prompted to pick click-and-collect with a prominent “free” message. At the same time, in the Netherlands, the highlighted benefit is sustainability—each tailored to local motivations and levels of disposable income. These nudges, Rooderkerk notes, are both low-cost and highly effective.

Fulfilment strategy is another lever. Swatch shows how simple, inventory-aware rules can avoid waste. When stock of a particular watch is low, the reservation option disappears from the site, preventing high no-show rates that tie up valuable inventory and reduce availability. This inventory-sensitive approach decreases operational friction and protects margins.

Store layout is another underused but powerful optimisation opportunity. Working with Coolblue, a Dutch consumer electronics retailer, Rooderkerk examined how the physical placement of click-and-collect points can meaningfully affect cross-sell potential. Early versions placed pickup desks near the entrance for convenience. However, that didn’t lead to additional purchases and resulted in scattered labour use. By routing certain high-value pickups—like smartphones—to spots near accessory displays, the retailer lifted cross-sell by 10 percentage points. This targeted rerouting was enabled by customer self-check-in kiosks and conditional logic, demonstrating that smart spatial design can significantly increase revenue per visit.

The last, and perhaps least discussed, pillar in this omnichannel shift is incentives, especially for ship-from-store. Rooderkerk points out a worrying 7% to 10% order cancellation rate due to insufficient inventory data or lack of store compliance. Often, stores deprioritise e-commerce orders when there are no incentives, or when picking disrupts in-store work. He has observed that without financial incentives, stores might cancel online orders to conserve inventory for themselves or to avoid additional tasks. This has clear effects: research shows that cancellations cause measurable drops in future customer spending and loyalty, even in high-frequency areas like grocery.

Solutions need to align technology with human incentives. Companies like Adidas have rolled out reward-based routing, sending orders to stores with strong compliance and fulfilment performance. Walmart and Target, for their part, are relying heavily on real-time inventory accuracy as a key routing factor. Rooderkerk’s findings show that orders sent to stores with verifiable stock availability achieve much higher fulfilment rates and customer satisfaction. Bonus systems linked to order volumes, real-time traffic signals, and available labour are additional factors being tested to fine-tune this orchestration layer.

As omnichannel optimisation turns channels into levers—nudges, routing, spatial design, and incentives—the next question is where those levers have the greatest force. That answer sits in the store network: the physical footprint that doubles as a fulfilment node, service stage, and brand amplifier. To make optimisation real at scale, retailers must decide when to open, resize, relocate, or densify. The following section explores how to architect that footprint for both growth and profitability.

Leveraging an omnichannel store network

The much-talked-about halo effect—the idea that opening stores lifts nearby online sales—is often exaggerated. Using the example of Warby Parker in the U.S., Rooderkerk notes that digitally native brands can indeed see halo effects because their stores act as showrooms, physical billboards, and trust anchors. For Warby Parker, which initially had low brand awareness and a strong reliance on showrooming, store openings served as a catalyst for growth across all channels.

However, this effect depends on context. In Rooderkerk’s research with Coolblue, which has 90% brand awareness in the Netherlands, no meaningful halo effects were observed after domestic store openings. In fact, online sales were more often cannibalised than expanded. But when Coolblue entered new markets—Belgium and Germany—halo effects did appear. This suggests that halo dynamics are most likely in low-awareness markets, where a physical presence helps build visibility, trust, and brand familiarity.

Rooderkerk also cautions against flawed internal analyses that credit all post-opening growth to the store, without isolating organic growth that would have happened anyway. He adds that misclassifying click-and-collect orders as purely online can distort how a store’s impact is evaluated, since many of these purchases depend heavily on in-store experience, upselling, and service.

Beyond opening new stores, Rooderkerk proposes a wider framework for store network strategy that includes expansion, downsizing, relocation, and densification. In particular, densification—adding smaller stores closer to high-density customer segments—is becoming a strategic frontier. Smaller formats enable retailers to target specific stages of the customer journey, reduce capital intensity, and increase proximity to key demographics.

These smaller stores can follow two main models:

- The first focuses on specific touchpoints in the journey, offering services like advice, pickup, or returns without holding full inventory. Nordstrom Local is a clear example, providing click-and-collect, tailoring, and return services in compact urban spaces. Similarly, IKEA’s “Plan & Order” stores in central Paris allow city dwellers without cars to plan complex purchases like kitchens without visiting large suburban warehouses. These locations focus solely on configuration and consultation—products are then delivered to the customer’s home.

- The second model supports the full journey within a smaller footprint. Galeries Lafayette’s store in Paris’ 15th arrondissement illustrates this approach. Although much smaller than the flagship, it offers a curated yet comprehensive assortment tailored to local families. By combining proximity with personalisation, the store increases visit frequency and deepens loyalty. For many consumers, especially families, this localised convenience reshapes their preferred shopping journey.

Designing these compact stores for high engagement requires agility. Layouts must be modular so assortments can shift quickly with seasons or trends. Rooderkerk highlights Decathlon as best-in-class: the retailer dynamically adjusts floor space by sport based on the calendar, enabled by highly flexible fixtures.

But proximity alone isn’t enough. To succeed, small-format stores must act as gateways to the broader ecosystem. Staff need training in endless aisle capabilities to access online inventory. Technologies that power smart recommendations or real-time inventory lookups can bridge physical and digital channels. However, services like ship-to-store or buy-online-return-in-store should be adopted carefully. While attractive to customers, these models carry significant cost and operational risk. Rooderkerk warns that returns, in particular, can overwhelm store teams and harm the shopping atmosphere—unless they are clearly segmented and potentially monetised through smart conversion efforts.

Deployed with rigorous measurement and clear roles, store networks become the most tangible arena where omnichannel optimisation compounds.

Conclusion: from “everywhere” to “the right where”

Omnichannel is no longer about being everywhere; it is about being decisive—prioritising the journeys that matter, removing the frictions that don’t pay, and steering customers to the touchpoints that maximise both profitability and equity. The maturity path shows that progress stalls when organisations stop at integration; value unlocks when orchestration becomes intentional, incentives are aligned, and stores are treated as precision instruments rather than blunt expansion. With rigorous measurement (including a sober view of the halo effect), role-based formats, and inventory-aware rules, the store network is where strategy meets unit economics. Retailers that iterate their nudges, layouts, routing, and incentive systems—and redeploy their footprint via relocation, downsizing, and densification—won’t merely follow customer behaviour; they will shape it, profitably. In fact, this relates to a simple truth: optimising customer journeys and reinventing the store network are not parallel projects, but interdependent levers of transformation.

Credits: IADS (Selvane Mohandas du Ménil)

IADS Exclusive: In Riyadh, department stores are trying to carve their place between souks and supermalls

IADS Exclusive: In Riyadh, department stores are trying to carve their place between souks and supermalls

CLICK HERE TO SEE PHOTOS OF RIYADH MALLS

As Chalhoub Group stated during the IADS CEO meeting in Dubai earlier in 2023, Saudi Arabia stands out as one of the Middle East’s most dynamic retail markets, undergoing rapid transformation fueled by Vision 2030’s drive to diversify the economy beyond oil[1].

In 2024, the Saudi retail market reached approximately USD 270.8 billion, with forecasts projecting growth to USD 408.7 billion by 2033 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.2%. The retail landscape has shifted from a dominance of traditional souks and small traders to a more organised and modern format, adapted to the needs of an urban, digitally savvy population (83% of Saudis live in urban areas, 98% of Internet traffic is done via smartphones) and making the most of an increasing consumer spending, especially among youth, expected to account for 75% of retail spending by 2035.

E-commerce is a significant growth engine, with online retail reaching an estimated market size of USD 8.7 billion in 2023 and experiencing a 32% CAGR over the past five years. Apparel, beauty, and food and drink are among the leading online categories, with apparel alone generating USD 4.18 billion in online sales. Substantial investments in omnichannel strategies, digital payments, and experiential retail concepts further energise the retail ecosystem.

This robust growth positions Saudi Arabia as a regional retail powerhouse, attracting local and international retailers considering entering, or strengthening their positions, in KSA. Taking the opportunity of conferences in the country, the IADS visited a selection of malls in Riyadh to understand the market and how department stores are faring there. From the most traditional malls (Olaya Mall, Panorama Mall), to the more Dubai-like (Cenomi Nakheel Mall), luxury-oriented (Al Faisaliah, Kingdom Centre, Solitaire), and experiential (Via Riyadh) ones, it is clear that there is room for the unity of space, supply and time that the department store format offers, much more than just for Harvey Nichols Riyadh and Al Rubaiyat.

Olaya Mall, Panorama Mall: two very different ways of being “traditional”

Olaya Mall is located in Riyadh's bustling Al Olaya district, a central business and retail hub of the Saudi capital which also includes the Kingdom Centre, just across the road, Al Rubaiyat, a fashion and lifestyle department store, and, a little further, Al Faisaliah mall (where Harvey Nichols is located) and the Panorama mall (where Etre, a fashion and luxury multi-brand store, is located).

Launched in 2000 by the AlMogren group, it was the first mall in Saudi Arabia to introduce international brands in the city, two years before the Kingdom Centre. It is now recognised for its family-friendly atmosphere, offering an appropriate environment for shopping and dining. It has a large food court that includes a mix of local and international fast-food chains, dedicated children's play areas, and shops that mostly showcase women’s apparel.

While, in theory, the mall benefits from its proximity to luxury hotels and business centres, making it accessible and attractive to locals and tourists, its current state and design make this unlikely.

Although the building remains pristine, its dated design betrays the era in which the mall was conceived. Several tenants wisely operate double façades—opening both to the parking lot and the interior concourse—but the shopfronts march down unbroken, monotonous corridors with no pauses for surprise or variety. Almost every retailer sells one thing—women’s dresses—so the offer has narrowed over time, appealing to a single product category and a single audience. The result is a mall frozen in the early phase of Western-style retail in the Gulf, a stark counterpoint to the more progressive Kingdom Centre just across the road.

Located 10 minutes away by car from Al Olaya, and a stone's throw from the King Khalid Grand Mosque, Panorama Mall represents another way of looking at tradition in the mall business. It was opened in 2010 on 130,000 sqm, developed by Mohammad Al Habib (a real estate company founded in 1972 with a track record of 50 projects in KSA) for the account of Aswaq Almustaqbal Company, the owner until 2020, when all stakes were sold to Borouj International Company for €23m. Leasing company Hamat Holding, is managing the property.

Panorama Mall is known for its panoramic facade, reinforcing its status as a visual landmark. The retail mix at Panorama Mall is robust and diverse, featuring over 200 stores that cater to a broad audience: luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Chopard, and Rolex share the space with high-street names like Zara, H&M, and Marks & Spencer. Speciality boutiques and high-end jewellers enhance the shopping experience, while the presence of the Danube Hypermarket, Jarir Bookstore, various electronics and home décor complete the offer.

What makes it unconventional (and, from our point of view, exaggerated) is the amount of space dedicated to experience[2]. While every retailer in the world knows the value of such space these days, Panorama Mall offers an experience on steroids: not less than 7,325 sqm is dedicated to one of the region's largest Sparky’s indoor amusement parks, attracting families in crowds. The mall also houses an AMC cinema and a food court oriented towards international fast food, conveniently located near the amusement zone. As a consequence, while such a heavy focus on family entertainment creates an sizeable traffic, it also seems disconnected from some parts of the mall, such as the luxury section with surprising adjacencies (Dior near Steve Madden, Chanel near Tumi), not to mention Etre, a multi-brand store that used to be fashion oriented and which now only focuses on home.

Panorama’s ambition mirrors its façade: broad, impressive, but unfocused. Families flock to Sparky’s, teens queue for AMC blockbusters, and luxury shoppers weave past sneakerheads under one roof that tries to please everyone. Yet history has shown that malls that trade distinction for dilution eventually lose both edge and audience. Panorama Mall may still glitter in 2025 Riyadh, but without a more deliberate point of view, it could be rehearsing the very script that closed so many U.S. anchor stores before the final curtain fell.

Olaya and Panorama stand side by side in this “traditional mall” section because—despite their opposite tactics of monotony versus maximalism—both cling to the same first-generation, one-size-fits-all template that newer retail formats have already begun to abandon.

Raising the bar: Cenomi Nakheel Mall

Opened in 2014 by Arabian Centres (a Riyadh-based real estate company, developer, owner, and operator of shopping malls in the Middle East trading under the Cenomi Centres brand), Al Nakheel Mall rapidly became a local reference. In 2015, the mall received awards from the International Council of Shopping Centres (ICSC) in the New Media/emerging Technology Marketing and Design and Development categories.

Cleverly situated along major roads leading into Riyadh and relatively far away from the Olaya catchment zone (which is crowded with four malls), Al Nakheel Mall attracts more than 200,000 visitors weekly, including many Riyadh residents, thanks to its visitor-friendly, single-level design spanning 370,000 square meters as well as a location ensuring easy access by car or private car services like Uber or Careem.

The mall's architecture is noteworthy for its walkways and design, which incorporate open spaces and intimate corners, allowing for a comfortable shopping experience. Accessible through eight gates, it is composed of two large wings, hinged on a central food court (relatively smaller than other malls). It includes family activities on the first floor: Muvi Cinemas, Sparky's, and Playnation playgrounds. The wings, which are inviting and perfectly maintained, are large enough to have stands in the middle, either for small accessories or refreshments.

The retail space boasts a selection of high-end luxury brands such as Chanel and Gucci, alongside popular international chains like Zara (located in a spectacular and central store) and H&M and a surprising array of Turkish brands (LC Waikiki, Kahve Dünyası…). Overall, the offer is lifestyle- and aspirational-oriented, and complete with experiences (a Jamie Oliver cooking school or an Australian restaurant). Essential services such as banks, pharmacies, and customer service desks further enhance its functionality and visitor convenience.

Despite a significant number of hoardings hiding empty units, the mall felt crowded during the visit, and many shopping bags were in sight. Compared to the two previous malls, this one felt modern, well-curated, and organised, competing with other successful regional generalist malls[3].

Going upscale: Kingdom Centre, Solitaire, Al Faisaliah

The Kingdom Centre, a symbol of modern Riyadh at the heart of the city in Olaya, was designed by Ellerbe Becket and completed in 2002. It is an iconic structure distinguished by its almond-shaped tower, which reaches a height of 302 meters, making it one of the tallest buildings in the city (and the third-tallest building with a hole worldwide). The tower's design is characterised by an inverted catenary arch, capped by a glass skybridge that offers panoramic views of Riyadh.

This mixed-use complex includes commercial, residential, and retail spaces. The tower comprises office spaces, a five-star Four Seasons Hotel, and luxury residences. It also includes the King Abdullah Mosque on the 77th floor, the world's highest mosque from ground level. At the tower's base, two symmetrical wings extend east and west, encompassing landscaped public gardens and a mall that spans 56,000 square meters across three levels.

This mall is a key feature of the complex and was inaugurated in 2001. It houses 161 stores, including a wide range of luxury brands, with a general design meticulously tailored to an affluent clientele. Interestingly, while in the past the mall housed a Debenhams and a Saks Fifth Avenue store, both of which closed a long time ago, only mono-brand stores are present, without any non-luxury anchor. During the visit, the mall was being revamped with quite a number of hoardings hiding units and part of the structure. Another notable feature is the food court on the top floor, “Al Mamlaka Social Dining”, where customers must pay an entry fee.

Solitaire, located in another catchment area up north in the city (near the Kingdom Hospital and the Financial District), is a new multi-use lifestyle complex covering over 65,000 square meters. Inspired by a geode, its design features an angular stone façade that evolves into a crystalline interior, creating a striking experience.

The complex includes three aboveground levels dedicated to retail, food and beverage, entertainment, wellness, and sports and three levels of basement parking. This layout caters to a diverse clientele, including high-net-worth individuals and expatriates living in nearby residential compounds. The North Plaza features fast-fashion brands, casual dining, and entertainment, while the South Plaza focuses on luxury retail and fine dining.

Sustainability is integrated into the mall design through wind towers for climate control, using mechanical fans to circulate air and offering a passive cooling solution. Similarly, water features, including misting elements, contribute to a cooler environment. Therefore, it is unsurprising that such a commitment has encouraged the Chalhoub Group to team up by bringing in a selection of luxury brands it operates in joint ventures, including Loewe, Celine, Fendi, or Tiffany & Co.

The most surprising during the visit was the fact that, even though almost no boutiques were open by then, with scaffoldings in the middle of the passageways and a strong smell of glue, the mall was already crowded with passers-by and customers sitting at the few restaurants (including French Paris Society brand Perruche) and cafés already in operations (including Ladurée, Patchi or luxury chocolate maker Bateel). While the opening date was set for a few weeks later, locals explained that this showed the enthusiasm of the KSA clientele for new experiences and places (also suggesting that this enthusiasm can wane as fast as it arrives).

Interestingly, both Kingdom Centre and Solitaire share a notable characteristic distinguishing them from traditional mall developments worldwide: the absence of department store anchors. While these destinations excel in creating immersive luxury environments through curated mono-brand boutiques and experiential elements, neither has incorporated the retail stability of flagship department stores or hypermarket. This choice reflects a local retail aspect but may also present challenges for consistent foot traffic beyond the initial excitement.

This is not the case at Al Faisaliah Mall, not far from Kingdom Centre. After a brief stint as Mode Mall, it re-emerged under its original name to align with Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030. The mall covers a retail area of 35,600 square meters within the Al Faisaliah Centre complex. This mixed-use development also houses the 267-meter Al Faisaliah Tower (for a moment, the tallest in the country, before losing its crown to Kingdom Centre) and a five-star Mandarin Oriental hotel, which is directly connected. The mall's architectural design, crafted by Foster + Partners, emphasises modern aesthetics with a glass atrium offering panoramic city views across three levels.

A major point of differentiation is that the mall houses a Harvey Nichols store in addition to the usual brands (see below). The mall was painstakingly empty during the visit.

A completely different experience: VIA Riyadh

Welcome to another planet! VIA Riyadh is a mixed-use development located far from all the other locations, adjacent to the Ritz-Carlton hotel, and includes a St-Régis hotel. This complex, inaugurated in Q2 2023, combines high-end retail, hospitality, and entertainment facilities, using local stones and drawing inspiration from the Nadji architectural approach.

The exterior of VIA Riyadh is striking, with architectural elements that evoke a sense of grandeur and opulence. The development is conceived as a fort-like structure or a mountain, with spectacular buildings that create an impressive visual impact upon arrival. Inside, the design maintains this high level of quality, featuring multiple distinct spaces that are large and elegantly staged.

VIA Riyadh is not about scale, but experience. At its heart is MWAZ, a spectacular multi-brand concept store displaying niche and rare brands. The store has high-tech displays and screens that contribute to its avant-garde presentation.

In the rest of the mall, the retail section only features 25 upscale shops, presenting international and local brands (from Brandon Maxwell to Elie Saab), art galleries (Richard Orlinski, Phoenix Ancient Art), a robust dining scene of 17 restaurants (including UK's Sexy Fish, US’ Spago, and the French Les Deux Magots) and seven cinemas each offering unique thematic experiences. The -1 level houses a car lounge showcasing brands like Ferrari and Porsche, a concierge service, and the Via Mercato luxury food market.

VIA Riyadh is designed as a human-scale luxury mall, creating an experience centred around relaxation and high-end retail. The absence of a dominant anchor store, apart from Zegna and MWAZ, emphasises a curated approach to luxury shopping. However, questions remain about the foot traffic and how the destination qualifies its market appeal, given its location outside the city near gated compounds. The place was empty during the visit.

And what about department stores?

While malls are omnipresent (up to 18 in Riyadh only), the department store format is not that common.

Harvey Nichols at Al Faisaliah Mall is the most prominent representative of this format. As visitors enter the mall, they are greeted by a prominent storefront featuring large display windows and calls to action for click-and-collect. This creates an inviting entrance adjacent to brands like Boss and Cartier.

The ground floor is dominated by a strong emphasis on fragrances, with a series of branded concept stores dedicated to perfumes. Visitors encounter a tunnel-like layout where brands such as Dior and Guerlain are creatively interwoven, a rarity.

The basement level was undergoing renovations at the time of visit. The first floor displayed a well-curated selection of women’s RTW brands within a concept unique to Harvey Nichols. The RTW area is divided into two main sections near the escalator, offering a luxurious ambience akin to an apartment setup, transitioning smoothly into a more generic yet well-executed section. This area features a selection of high-end brands, stopping just short of ultra-luxury. A dedicated zone for local designers presents shoes and accessories, though this section remains underdeveloped compared to others.

On the second floor, the focus shifts to children's luxury multi-brand concepts and leisure activities. This includes kid’s brands not featured in the women's sections. The central sale areas are effectively designed, with the athleisure zone featuring brands like Veja and Axel Arigato, a corner displaying The Edit LDN concept (an original Harvey Nichols London feature), and a transition into home goods and streetwear collections. Nearby, the men's section is somewhat compact, featuring a concept store, sneaker laundry, design area, and a t-shirt bar towards the back, all looking cluttered. Probably due to space issues, an area on that floor is dedicated to a couture-like women's RTW salon, complete with shoes, bags, and dresses from brands such as Oscar de la Renta. The store becomes somewhat chaotic toward the back, with a t-shirt bar adding to the eclectic mix.

While the store was impeccable during the visit, it was also very empty, with VM employees ironing products on the sales floor and staff dressed casually, which fostered an approachable atmosphere but could also lead to confusing them with visitors. The omnipresence of promotional material for online shopping and up to 60% discounts also suggested that the business was not so fluid.

Al Rubaiyat is a concept standing halfway between the department store format and a concept store, and is located across the road in front of Kingdom Mall. Originally a company from Jeddah, Al Rubaiyat opened the Riyadh location in 2019, spanning 2,100 sqm, with a concept crafted by Virgile + Partners. It focuses primarily on luxury womenswear, showcasing brands such as Gucci, Balenciaga, and Saint Laurent.

A notable security measure was immediately apparent upon entering: a guarded entrance where customers had to leave their bags (a feature not seen elsewhere during the visits). The heightened security measures suggested a proactive stance on preventing theft, which may reflect broader concerns about inventory loss or a strategic effort to enhance the shopping experience by ensuring a safe and orderly environment.

The store was in the midst of a sales event, as indicated by the ubiquitous sales signs and densely packed clothing racks. The store layout was somehow confusing, with kids' offerings intertwined with women’s RTW and the dressy part upstairs and quite visible: anyone looking for evening gowns would be immediately spotted by other visitors.

While the store was beautiful, it also felt packed with products and only crowded with hostile salespersons more occupied with preventing theft than offering their services. While the timing may not have been the best (at the end of the day), this visit was the most unconvincing of the whole tour.

It seems that Riyadh’s two flagship department-store experiments (Harvey Nichols and Al Rubaiyat) expose both the promise and the peril of a retail format that has not yet truly taken root in the Kingdom. Each strives for curated luxury, yet both compensate for thin footfall with deep markdowns, dense merchandising, and conspicuous security in Al Rubaiyat’s case. The result is a shopping experience that feels more guarded than guided, more promotional than aspirational.

Today's Riyadh retail landscape is defined by malls that either cling to the comfort of tradition or chase the latest trends with maximalist ambition. Across the spectrum—from the single-category monotony of Olaya Mall, to the entertainment-driven sprawl of Panorama Mall, to the carefully curated luxury of Kingdom Centre and VIA Riyadh—a common thread emerges: the absence, or underperformance, of true department stores as anchor retail experiences.

The limited experiments so far—Harvey Nichols and Al Rubaiyat—have only scratched the surface of what a department store could mean for Riyadh. Both stores display flashes of curation and aspiration but are hobbled by a reliance on deep discounts, dense merchandising, and a guarded, transactional atmosphere. Far from the bustling, service-rich hubs in other world capitals, these stores remain peripheral, their value yet to be fully articulated or realised.

Yet, beneath the surface, the opportunity remains. While Saudi shoppers have grown accustomed to the convenience and spectacle of malls, the department store format—when reimagined—offers something that no mall or boutique can replicate: an all-under-one-roof experience built on true curation, seamless service, and coherent storytelling across categories and brands. In an environment where retail destinations either dilute their identity or fragment their offer, a department store with a clear point of view can become an oasis of discovery, personalisation, and hospitality.

For a new generation of Saudi consumers—curious, globally connected, and eager for differentiated experiences—a department store that embraces curation, brings together international and local brands, and delivers best-in-class services (from personal shopping to seamless omnichannel integration) could unlock a form of value they do not yet suspect. It is not about nostalgia but anticipation: meeting needs and desires that have yet to be fully expressed. We believe that in Riyadh, the space is still open for a department store that dares to define itself, not by what has been tried and failed, but by what has not yet been imagined.

[1] Vision 2030, launched in 2016 under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, is the country’s flagship development plan. It is a comprehensive blueprint aimed at transforming Saudi Arabia’s economy, society, and government, and is structured around three main pillars: a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious nation. The plan includes 96 strategic objectives, focusing on economic diversification, reducing dependence on oil, empowering citizens, fostering investment, and enhancing the Kingdom’s global role.

[2] And yet, the IADS is a fervent supporter of experience in retail.

[3] Cenomi Centres is not a rookie: the company operates 22 malls in KSA, including the Mall of Arabia in Jeddah and the Mall of Dharan among the most iconic ones alongside Nakheel Mall Riyadh.

Credits: IADS (Selvane Mohandas du Ménil)

IADS Exclusive– The Saks saga: Heritage, mergers, and risk in the making of America’s new luxury giant

IADS Exclusive– The Saks saga: Heritage, mergers, and risk in the making of America’s new luxury giant

The formation of Saks Global in July 2024 was positioned as a landmark moment in luxury retail, a merger meant to give Saks and Neiman Marcus dominance in a shrinking department store business. Backed by tech allies Amazon and Salesforce, and reinforced by a partnership with Authentic Brands Group, the deals promised operational synergies, expanded customer and brand reach, and digital acceleration. So much has happened since then, and behind the headlines lies a more fragile reality. What was touted as a strategic move may, in fact, be a high-stakes gamble with a limited margin for error.

At the time of the merger, the IADS took stock of the freshly minted Saks Global company. A year or so later seemed to be the right time to pause and reflect on Saks Fifth Avenue’s history, a history marked by mergers from its inception in 1867 to its struggles in 2025.

A store is born: The foundations of Saks

Innovation, family legacy, and the first major merger that shaped Saks

In 1867, at the age of 20, Andrew Saks and his brother opened a men's clothing store in Washington, D.C. Early on, the small company implemented what would be recognised as department store innovations, such as banning bargaining, merchandise returns, and product catalogues. By 1897, Saks & Company had six stores, including one in Washington and two in New York City. In 1902, while Andrew’s sons, Horace and William, had joined the family business, they secured a long-term store lease at New York’s Herald Square. When Andrew died in 1912, Horace took over management of the company.

In 1923, Saks & Company merged with department store company Gimbel Brothers, Inc., which was owned by Horace’s cousin, setting the stage for future expansion. Having their Herald Square store rent doubled, Horace Saks and Bernard Gimbel decided to relocate their business. In September 1924, they opened New York’s iconic store at 611 Fifth Avenue, marking the first time a large retailer had established a presence in what was then primarily a residential district. Adam Gimbel (Bernard’s cousin) took over the leadership from 1926 when Horace Saks died. In 1931, a couture salon opened its doors, Salon Moderne, which soon ranked among New York’s most glamorous retail spaces. Ran by talented Adam’s wife Sophie, the salon sold her in-house designs alongside fashion from Chanel, Vionnet, Schiaparelli and more. By offering the finest quality, as well as an extraordinary programme of customer services, Saks Fifth Avenue soon became the reference for taste and elegance.

During the Great Depression, Saks proved relatively resilient thanks to its luxury positioning and the instalment options offered to customers, then a common practice among department stores. These challenging times also triggered innovation. Adam Gimbel revolutionised retail presentations by implementing creative solutions. New display techniques were introduced, along with cost-cutting practices such as using cardboard and papier-mâché instead of wood, stone and metal.

By 1940, Saks Fifth Avenue had 12 locations: four flagship stores (in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles’ Beverly Hills and Detroit) and seasonal resort stores. During World War II, in response to changing customer needs, Saks opened Navy and Army shops, which later evolved into University shops after the war, catering to the Ivy League communities.

The mall era and corporate hands