IADS Exclusive: From orchestration to reinvention, how omnichannel mature

Retailers have spent the last decade chasing the promise of omnichannel, often equating it with being everywhere at once. But the real challenge today is not ubiquity—it is focus. The most advanced players are learning to guide customers toward journeys that create value, while reshaping their store networks into engines of proximity, trust, and fulfilment. Omnichannel is no longer just about touchpoints; it is about rethinking the very infrastructure of retail.

The IADS has published several articles on the topic, including from Dr Christopher Knee, the Association’s honorary advisor. To go further and make conceptual advances, we invited Robert Rooderkerk, an Associate Professor at Erasmus University (Rotterdam), to give IADS CEOs an idea of where research about Omnichannel stood at the time. By a fortunate coincidence, his lecture took place the very week when he published his latest article in the Harvard Business Review, When omnichannel retailers don’t deliver what customers ordered.

Rooderkerk holds an M.Sc. in Econometrics with a specialisation in logistics from Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Ph.D. in Marketing from Tilburg University – both earned with cum laude distinction. His research focuses on the intersection of marketing and operations, addressing critical challenges in omnichannel retail and retail analytics.

Drawing from collaborative academic research, insights from management journals and popular media, and conversations with practitioners across industries such as apparel, consumer electronics, grocery retail, and DIY— he offered a fresh view on the steps department stores could take to become truly omnichannel and remain competitive against specialist retailers and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) brands.

Introduction: the new competitive reality in omnichannel retail

Today, department stores face competition from many directions. Digitally native brands are opening their own flagship stores to protect their brand and collect richer customer data. Specialists like Sephora are winning by offering very deep product ranges and seamless cross-channel experiences. At the same time, luxury online marketplaces are setting new standards for what customers expect.

In this context, department stores can’t just keep up with omnichannel capabilities—they need to use those tools to guide customer behaviour. In other words, they must stop relying only on defensive strategies and instead take an active role in shaping customer experiences that increase profitability. To achieve this, Rooderkerk suggests two angles.

The first one is to push omnichannel optimisation forward: the goal of omnichannel is no longer just connecting all channels but actually optimising them—steering customers toward the paths that are most valuable for the retailer. This can mean higher profitability, better efficiency, or progress toward sustainability. To make this work, retailers need a more precise understanding of how customers move between channels and touchpoints. The most advanced companies have gone past simply allowing every possible shopping journey. Instead, they now nudge customers to channels or combinations of channels that bring higher margins, reduce returns, or balance inventory across the network. They use data to shape behaviour through personalised offers, dynamic user experiences, and fulfilment strategies that serve business goals.

The second one is to make store networks work through smaller formats. Smaller formats are becoming strategic assets: lower cost, highly flexible nodes for last mile, localised assortments, and experiential service—especially in cities. Rooderkerk insists that store strategy and digital strategy can no longer be separated. Each store should not only be judged on sales per square metre but also on how it supports customer experience, delivery efficiency, and brand visibility across all channels.

The omnichannel evolution: moving into the optimisation stage

The term “omnichannel” is often misunderstood—if not outright misleading. Robert Rooderkerk emphasises that omnichannel is not about being present in every possible place at once, but about being present where it matters, delivering value to both the customer and the business simultaneously. This shift in perspective is essential.

According to Rooderkerk, the industry’s fixation on perfectly seamless customer journeys has pushed many companies into strategies that don’t make money. Removing every bit of friction can look customer-first, but if there’s no solid business reason, it becomes financially unsustainable. The goal isn’t to abolish all friction—it’s to remove friction intelligently where it supports broader strategic objectives. In this sense, omnichannel isn’t a tech spend or a tactical add-on—it’s a mindset—a mindset of continuous evolution, iteration, and optimisation.

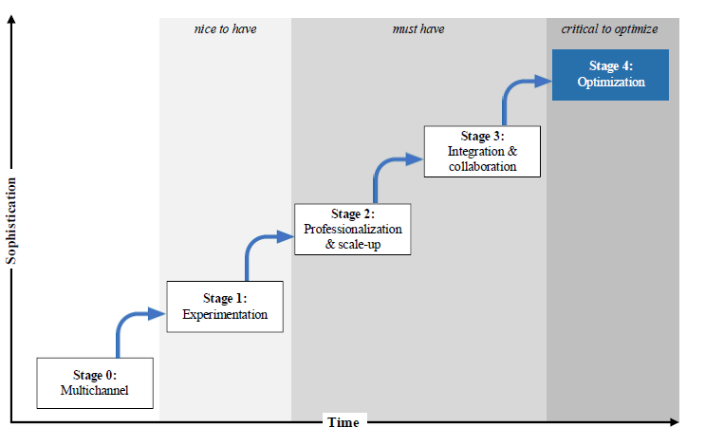

Through a broad research effort with C-minus-one level leaders (such as heads of omnichannel, operations, and marketing) across categories from luxury to consumer electronics, in 2025, Rooderkerk outlined a maturity model that most companies are currently moving through.

Credits: Robert Rooderkerk, 2025

The journey typically begins in a fragmented, multichannel phase, where online and offline channels are siloed and serve different customer segments. This setup fell short during the COVID-19 pandemic, when retailers rushed to stand up click-and-collect using a mix of manual workarounds and disconnected systems. That time was the “experimentation” phase: it worked, but it wasn’t efficient.

As retailers progressed, they moved into what Rooderkerk calls the “ramping up” stage—scaling services like same-day or even same-hour click-and-collect, expanding geographic reach, and increasing speed. Still, most companies today are stuck in this phase or the next, known as “channel integration.”

This third stage focuses on omnichannel order orchestration—using centralised systems to choose the best fulfilment nodes, whether stores or distribution centres, based on stock availability, distance, and delivery efficiency. Yet many organisations are still held back by internal silos between digital and physical teams, with ongoing “tribal” conflicts over budgets, authority, and strategy.

The move from a channel-led to a customer-led organisation is signalled by customer journey segmentation. That means spotting and investing in the most valuable or frequent journeys based on transaction volume or customer value. Instead of trying to optimise every possible journey, the most forward-looking retailers focus on the ones with the most significant return potential.

But the most advanced retailers don’t just support these journeys, they shape them. This higher level of maturity, which Rooderkerk calls “omnichannel optimisation,” is about steering customers toward the channels and touchpoints that improve profitability or customer equity. Strategic guidance might mean encouraging in-store visits in areas where delivery performance is weak, or nudging customers away from home delivery when in-store interactions offer better upsell opportunities or long-term loyalty benefits.

Holland & Barrett, for example, uses different nudges by market to influence channel selection. In the UK, customers are prompted to pick click-and-collect with a prominent “free” message. At the same time, in the Netherlands, the highlighted benefit is sustainability—each tailored to local motivations and levels of disposable income. These nudges, Rooderkerk notes, are both low-cost and highly effective.

Fulfilment strategy is another lever. Swatch shows how simple, inventory-aware rules can avoid waste. When stock of a particular watch is low, the reservation option disappears from the site, preventing high no-show rates that tie up valuable inventory and reduce availability. This inventory-sensitive approach decreases operational friction and protects margins.

Store layout is another underused but powerful optimisation opportunity. Working with Coolblue, a Dutch consumer electronics retailer, Rooderkerk examined how the physical placement of click-and-collect points can meaningfully affect cross-sell potential. Early versions placed pickup desks near the entrance for convenience. However, that didn’t lead to additional purchases and resulted in scattered labour use. By routing certain high-value pickups—like smartphones—to spots near accessory displays, the retailer lifted cross-sell by 10 percentage points. This targeted rerouting was enabled by customer self-check-in kiosks and conditional logic, demonstrating that smart spatial design can significantly increase revenue per visit.

The last, and perhaps least discussed, pillar in this omnichannel shift is incentives, especially for ship-from-store. Rooderkerk points out a worrying 7% to 10% order cancellation rate due to insufficient inventory data or lack of store compliance. Often, stores deprioritise e-commerce orders when there are no incentives, or when picking disrupts in-store work. He has observed that without financial incentives, stores might cancel online orders to conserve inventory for themselves or to avoid additional tasks. This has clear effects: research shows that cancellations cause measurable drops in future customer spending and loyalty, even in high-frequency areas like grocery.

Solutions need to align technology with human incentives. Companies like Adidas have rolled out reward-based routing, sending orders to stores with strong compliance and fulfilment performance. Walmart and Target, for their part, are relying heavily on real-time inventory accuracy as a key routing factor. Rooderkerk’s findings show that orders sent to stores with verifiable stock availability achieve much higher fulfilment rates and customer satisfaction. Bonus systems linked to order volumes, real-time traffic signals, and available labour are additional factors being tested to fine-tune this orchestration layer.

As omnichannel optimisation turns channels into levers—nudges, routing, spatial design, and incentives—the next question is where those levers have the greatest force. That answer sits in the store network: the physical footprint that doubles as a fulfilment node, service stage, and brand amplifier. To make optimisation real at scale, retailers must decide when to open, resize, relocate, or densify. The following section explores how to architect that footprint for both growth and profitability.

Leveraging an omnichannel store network

The much-talked-about halo effect—the idea that opening stores lifts nearby online sales—is often exaggerated. Using the example of Warby Parker in the U.S., Rooderkerk notes that digitally native brands can indeed see halo effects because their stores act as showrooms, physical billboards, and trust anchors. For Warby Parker, which initially had low brand awareness and a strong reliance on showrooming, store openings served as a catalyst for growth across all channels.

However, this effect depends on context. In Rooderkerk’s research with Coolblue, which has 90% brand awareness in the Netherlands, no meaningful halo effects were observed after domestic store openings. In fact, online sales were more often cannibalised than expanded. But when Coolblue entered new markets—Belgium and Germany—halo effects did appear. This suggests that halo dynamics are most likely in low-awareness markets, where a physical presence helps build visibility, trust, and brand familiarity.

Rooderkerk also cautions against flawed internal analyses that credit all post-opening growth to the store, without isolating organic growth that would have happened anyway. He adds that misclassifying click-and-collect orders as purely online can distort how a store’s impact is evaluated, since many of these purchases depend heavily on in-store experience, upselling, and service.

Beyond opening new stores, Rooderkerk proposes a wider framework for store network strategy that includes expansion, downsizing, relocation, and densification. In particular, densification—adding smaller stores closer to high-density customer segments—is becoming a strategic frontier. Smaller formats enable retailers to target specific stages of the customer journey, reduce capital intensity, and increase proximity to key demographics.

These smaller stores can follow two main models:

- The first focuses on specific touchpoints in the journey, offering services like advice, pickup, or returns without holding full inventory. Nordstrom Local is a clear example, providing click-and-collect, tailoring, and return services in compact urban spaces. Similarly, IKEA’s “Plan & Order” stores in central Paris allow city dwellers without cars to plan complex purchases like kitchens without visiting large suburban warehouses. These locations focus solely on configuration and consultation—products are then delivered to the customer’s home.

- The second model supports the full journey within a smaller footprint. Galeries Lafayette’s store in Paris’ 15th arrondissement illustrates this approach. Although much smaller than the flagship, it offers a curated yet comprehensive assortment tailored to local families. By combining proximity with personalisation, the store increases visit frequency and deepens loyalty. For many consumers, especially families, this localised convenience reshapes their preferred shopping journey.

Designing these compact stores for high engagement requires agility. Layouts must be modular so assortments can shift quickly with seasons or trends. Rooderkerk highlights Decathlon as best-in-class: the retailer dynamically adjusts floor space by sport based on the calendar, enabled by highly flexible fixtures.

But proximity alone isn’t enough. To succeed, small-format stores must act as gateways to the broader ecosystem. Staff need training in endless aisle capabilities to access online inventory. Technologies that power smart recommendations or real-time inventory lookups can bridge physical and digital channels. However, services like ship-to-store or buy-online-return-in-store should be adopted carefully. While attractive to customers, these models carry significant cost and operational risk. Rooderkerk warns that returns, in particular, can overwhelm store teams and harm the shopping atmosphere—unless they are clearly segmented and potentially monetised through smart conversion efforts.

Deployed with rigorous measurement and clear roles, store networks become the most tangible arena where omnichannel optimisation compounds.

Conclusion: from “everywhere” to “the right where”

Omnichannel is no longer about being everywhere; it is about being decisive—prioritising the journeys that matter, removing the frictions that don’t pay, and steering customers to the touchpoints that maximise both profitability and equity. The maturity path shows that progress stalls when organisations stop at integration; value unlocks when orchestration becomes intentional, incentives are aligned, and stores are treated as precision instruments rather than blunt expansion. With rigorous measurement (including a sober view of the halo effect), role-based formats, and inventory-aware rules, the store network is where strategy meets unit economics. Retailers that iterate their nudges, layouts, routing, and incentive systems—and redeploy their footprint via relocation, downsizing, and densification—won’t merely follow customer behaviour; they will shape it, profitably. In fact, this relates to a simple truth: optimising customer journeys and reinventing the store network are not parallel projects, but interdependent levers of transformation.

Credits: IADS (Selvane Mohandas du Ménil)