Articles & Reports

Innovative Thinking Series: IADS interview with Scot Case (NRF) on Sustainability

Innovative Thinking Series: IADS interview with Scot Case (NRF) on Sustainability

Introduction

The IADS interviewed Scot Case, the Vice President of Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability at the National Retail Federation (NRF), who has been in the sustainability space since the mid-1990s. From his experience, sustainability is the intersection of three key aspects: business, environmental, and social issues.

Early on in our conversation, Scot shared that the sustainability space is constantly evolving. While in the 90s, the main focus regarding sustainability topics was around recycling, today the focus has shifted towards human rights and climate change issues. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that all of these topics are related in some way, it just depends on what is seen as important and to which player. It is much like an iceberg, only a piece of the issue is unveiled, the part that is being centred on by businesses or consumers, but not the much larger contributing factors that remain unseen or below the surface. A retailer, an individual, or a consumer will focus on one aspect of sustainability and not realise that all issues are intertwined and connected to a challenge that is much bigger than meets the eye.

Retail at the centre of sustainability

IADS - You made it clear at the 2022 Retail’s Big Show in New York that the word ‘sustainability’ is diluted. How do you personally define sustainability when applied to a retail business?

Scot Case - When we started this initiative at the National Retail Federation, the first key issue was to decide what an industry-wide definition looks like. After lots of conversations with retailers, we boiled it down to a simplified definition. Sustainability is creating net positive environmental, social, and community benefits. This net positive concept is similar to how one measures whether a business is profitable or not. At the end of the year, some parts of your business are making money, some parts are kind of breaking even, and some parts are losing a little bit of money. That's what sustainability looks like as well. Some aspects of the business are clearly generating all sorts of benefits and profitability. Other times there will be some costs from an environmental or social impact. But overall profitability is necessary to be able to fund the sustainability projects and initiatives that contribute to making the world a better place.

When companies start to consider sustainability as part of their business, they might only see it as a cost, but rather they should consider it as an investment. At one time retailers probably saw cash registers as a cost, but in the end, such initiatives are contributing to the longevity of the business and sustainability should be seen as the same. Retailers that consider sustainability as an investment are the ones that are prospering. The challenge is that this is a long-term investment, but some of the most significant players in the sustainability space started their journey 15 to 20 years ago, and now the rest of the industry is struggling to catch up.

IADS - You once said that “retail is at the centre of sustainability”. Can you elaborate on this opportunity and influence that retailers have in this space?

SC - Retail is not just the centre of sustainability, retail is the centre of the universe. Sustainability is just embedded in the space. A retailer's ultimate job is to find the best products to meet the needs of the consumer. Consumers want more sustainable products now that they understand that every single purchase has hidden human health, environmental and social impacts. Retailers are best positioned to understand where the best products are, what the hidden human health, environmental, and social impacts are, and then share that information with the consumer. Retailers have access to all the information and ultimately that's what retail is all about. Sustainability is just an additional layer of the story and an additional layer of information.

Advice to retailers: beginners to advanced

IADS - For retailers that have just started investing in sustainability initiatives, what do you believe is the most important area for them to focus on first?

SC- Albert Einstein suggested that you spend 90% of your time defining the challenge. You can achieve this by asking the right questions to figure out what information your consumers are seeking so that you as the retailer are asking the right questions of your suppliers. The reality is that not everyone has the answers yet, and that's okay! The main thing is to be honest and transparent. It is okay to include consumers in the sustainability journey by sharing that the business is attempting to trace the entire carbon footprint of everything sold or trying to trace the origins of all the cotton used, and the challenges that the company is facing to reveal such information. It is important to show that you are committed to making this kind of information available so consumers can make better and more informed decisions. That is an honest story that consumers tend to respond to. Don’t let perfection get in the way of getting started, no retailer started perfectly out of the gate. The history of retail is a history of failing, learning, and doing it again.

IADS - For retailers that have been working hard on their sustainability journey for years and feel like they are no longer playing defence when it comes to CSR topics, where can they go next to be leaders in the space?

SC - I think that even the largest players have realised there are limits to what they can accomplish on their own and that's why, at the National Retail Federation and at IADS, retailers are learning that maybe they should be collaborating on some of these things. Some of these issues pop up in pre-competitive spaces, so there are opportunities for the industry to be sending clear signals deep into supply chains, to consumers, and to regulators to understand what can be accomplished currently, what areas need attention, and where working together is necessary. I think the largest players have learned to collaborate to make sure we have the best sustainability metrics and standards for sustainable fashion, sustainable electronics, or sustainable luxury products. Collaboration is the fastest way to solve problems in the space.

Sustainable department stores

IADS - In your opinion, what does the sustainable department store of the future look like to you? How does it operate? Will it sell ‘new’ products or only offer circularly produced products? How will it achieve profitability?

SC - I think when you design sustainable retail and the department store of the future, you start immediately with your own operations. The focus is on creating a maximum benefit meaning reducing your energy use, going to a hundred percent carbon-free energy and carbon-free logistics. It is important to make sure it's embedded at the core of the business and what you directly control. The next phase is having very effective programs to work with suppliers so that suppliers clearly understand your definitions of sustainability, the metrics that you're using, how you're evaluating their products and their sustainability performance, not just how they're making those products.

Another piece is communicating really effectively with the consumer. Consumers have multiple definitions of sustainability. So it is the retailer's job to understand that and to be able to match what they have available for sale to influence consumer decisions towards sustainability. Retailers are exploring business models, such as rental, that reduce all of the environmental and social impacts of making a garment, while allowing the retailer to sell the same product multiple times.

The future of sustainability in retail

IADS - What are some trends or technologies that could empower sustainable retailers? What companies or solutions should retailers be looking to invest in? (RFID, connected garments, product passports, resale marketplaces, …)

SC - I think you've just named a couple of them. So a lot of these are blockchain-based. The ability to track with blockchain where the cotton from a shirt came from, where the factory was, what kind of dyes were used, who sold it, or when the item was returned or recycled is the key to success in sustainability. Any of these technologies that are collecting, validating, verifying, aggregating sustainability data are going to be really important for moving into the future.

We are also looking at the redesign of supply chains to meet the needs of those consumers, fascinated with the circular economy. Therefore reverse logistics gets very fascinating because it is no longer only about how to make sure these products that the consumer bought and no longer wants and needs doesn't end up in a landfill or in some foreign country being burned. It is about the ability to track, measure, quantify, aggregate and then make good use of that information.

Is there anything else that you would like to share with our members about projects that you are working on, advice you can offer, or opportunities in the space that we have not covered yet?

SC - I actually have a request for retailers all around the world to be sharing their sustainability stories with the rest of the industry. These really are, in many ways, pre-competitive concepts. So I encourage IADS members to share their sustainability opportunities, challenges, risks, headaches, and solutions. We're asking the same of our members so that we can build a global solution for the retail sector. As retail is the centre of commerce, I think there's a real opportunity for retailers to redefine what a sustainable future looks like.

Credits: IADS (Mary Jane Shea)

Retail Review: Beauty Concepts

Retail Review: Beauty Concepts

Keeping markets under close watch, IADS collected noteworthy beauty concepts from retailers around the world.

Check out how retailers are drawing customers into physical stores through new enticing design concepts, innovative experiences, expanded product offer, technology and fun.

Clinique Laboratories, China

The new retail concept from the skincare brand aims to personalize each customer visit. Customers have their skin analyzed before they enter the store thanks to a diagnosis made through a facial scanning system. The rest of the store experience is then determined by the result of the diagnosis: presentation of specific products and services, close to consulting, that will be unique for each customer.

MORE ON Clinique Laboratories, China

B+ Tube, Changsha

The shopping experience, organized throughout the 218 sqm store, allows teens to create social media as they shop, something which helps facilitate online to offline consumption. Sections are organized around the three basics of cosmetics: cleansing, foundation, and make-up. Each area hosts an education centre for customers to learn and experiment with the products through tutorials and videos.

Glossier, UK

Glossier, a ‘community-driven beauty discovery hub’, opened its first permanent location outside of the US. The design is playfully balanced between old and other modern materials and finishes, like perforated paneling and sculptural marble in Glossier’s identifiable millennial-pink hue. The heart of the store is the product testing area. Mirrors are inscribed with ‘You Look Good’ – Glossier’s confidence-boosting catchphrase. Meanwhile, a ‘Wet Bar’ encourages sampling of skincare and makeup.

H Beauty, UK

H Beauty stores by Harrods has price points suiting a vast array of consumers. “Magic Mirrors” leveraging augmented reality technology permit customers to virtually try on products and have images of their experimentation sent directly to their phones. Dedicated spaces labelled “Play” allow customers to have fun with hairstyling, product demos and makeup consultations.

Harmay, China

Once an online retailer, Harmay stores shake up the high-end cosmetics segment. Targeting savvy young consumers and fast developing in Chinese first-tier cities, Harmay has a solid reputation as an influential incubator of consumer trends. Harmay gained a reputation for creating design-led retail spaces, aiming to boost the shopping experience. The displays encourage self-serving shopping which captures the mindset of shoppers.

Joyce Beauty, Shanghai

Joyce Beauty at Lane Crawford, offering a serene refuge from the department store hustle and bustle, is dedicated exclusively to niche high-end cosmetics and fragrances. These brands (Dr. Barbara Sturm, Perricone MD, Augustinus Bader, RéVive, Floraïku and 111SKIN among others) show the growing appeal for prestige beauty.

more on JOYCE BEAUTY, Shanghai

MDC Next Door, Berlin

MDC cosmetics is pushing the beauty limits by offering luxury cosmetics, fine objects, small furnishings, ceramics, and jewelry. MDC cosmetic is a curated specialist shop for cosmetics and cosmetic treatments. You can find brands including Aesop, Image skincare, Susanne Kaufmann, malin+goetz, Santa Maria Novella, Frederic Malle, Escentric molecules, Emma S and many more.

Retterspitz, Nuremberg

One of Germany’s oldest pharmacy brands, offering a wide range of cosmetics and medical cosmetics that combine traditional healing expertise with modern standards and the latest scientific research. Retterspitz offers an immersive brand experience and personal customer service, while serving as a marketing tool to discover clientele’s preferences and shopping patterns.

MORE ON RETTERSPITZ , Nuremberg

The New Sanctuaries, Mexico City

Founded by Mexican designer, pharmacist and alchemist Tatiana Torrealba, The New Sanctuaries provides clean cosmetics for skin care, products that have a high energy frequency and coexist in harmony with nature. The brand is taking information from ancestral knowledge, clean beauty principles, transparency, nature and technology.

MORE ON THE NEW SANCTUARIES, MEXICO CITY

Product passports: bringing transparency to retail

Product passports: bringing transparency to retail

Introduction

In December 2021, the European Union announced plans to use digital product passports to boost the circular economy and to gain a better view on the full lifecycle of various products, including textiles. The overall goal would be to prevent these items from ending up in landfills and to keep them in circulation, either as broken down raw materials to be reused or to be repurposed. Nowadays, it is expected that products should last longer, be repairable, and be recyclable. The major problem is that the information revolving around product components and recyclability is easily lost, but the EU believes that these digital product IDs can be the change that industries need to better promote circularity.

Digital product passports: what is it and what for?

Digital product passports (DPPs) provide a way to digitally capture key information about an item and create a centralised bank where this information can be stored. Basically, it is a virtual tag that captures all information surrounding the product to bring transparency about materials used and overall impact to customers and manufacturers. According to Business of Fashion’s The State of Fashion 2022 report, product passports can be used to boost authentication, transparency, and sustainability by acting as a method to store and share information easily so that either customers or businesses interacting with the product can understand how it was made and what it is made of. According to the report, this technology should not be overlooked because approximately 2 out of 5 fashion executives plan to adopt product passports in 2022 or have already done so.

Communication stemming from these product passports will need to be two fold: addressing customer-facing needs and informing recycling or repair entities with technical information about the item's components or how to extend its life. Digital product passports tackle a few key issues around product information:

- Increased transparency: easily accessible product material information will facilitate the proper recycling and reparation of items.

- Improved life cycle sustainability: availability of detailed supply chain information from material grade, carbon footprint, repair instructions and components.

- Centralised bank of information: provides all necessary information needed by stakeholders such as governments, manufacturers, customers, and for those involved with the second-life of the product.

How can product passports be helpful to retailers?

As seen with NFTs and RFID, technology that enables brands to add a unique identity to each product is increasing in value and importance. These identification technologies are unlocking a lot of potential business cases that retail players find worth investing in. Interestingly, retailers that have already invested in RFID (radio-frequency identification), blockchain technology like NFTs (Non-fungible tokens), QR codes, and NFC (near-field communication can extend their use with product passports. Already this technology has allowed businesses to get a handle on counterfeiting as well as create better transparency across the supply chain, which addressed two major pain points for retailers.

Product passports can also extend the relationship between retailers and their products. Retailers are at a time where they are saying goodbye to the short-lived relationship between brands and products where brands and customers part ways completely following a sale. Customer-brand relationships have advanced, and harnessing the power of product passports gives brands the ability to continuously identify and monetize apparel products through circular business models such as rental, repair, resale, and recycle. This extension of their product’s life not only increases their potential for margins, but also unlocks access to new types of customers, such as Gen Z, who value affordable and sustainable products.

Examples of notable players powering product passports

A major player that is helping power connected products across fashion, apparel, and retail is Eon Group with their Internet of Things (IoT) platform which brings together partners to gather and share data. CircularIDs allow brands to have instant access to connected product data that is crucial for recycling and re-commerce. A mobile app allows users to scan products using RFID, NFC, or QR codes to access details ranging from the original sales price to the material content, with the ability to capture the resale channel as well. This database of information opens garments up to become more circular overall.

Eon Group’s service also increases the amount of communication surrounding garments between brands and consumers. Once a connected product is scanned, customers can access styling tips, instructions for resale, sustainability credentials, services for rental, among other things. The group has basically created a common language and formats for brands to communicate across the lifecycle of fashion products. Eon has already partnered with retail players such as the Yoox Net-A-Porter Group, H&M, and Pangaia

There have been additional efforts in connectivity for the retail industry. In 2020, Avery Dennison partnered with Certilogo, a digital authentication platform, to integrate the solution with Avery Dennison’s apparel labelling products so customers can verify product authenticity via their smartphones through a series of questions. Also, start-up Wiliot offers bluetooth-enabled microchips the size of a stamp that have the ability to sense, compute and communicate. These chips have the ability to report every condition and interaction they face to the cloud in real-time, and are even self-powered using radio frequency!

The limits: standardisation needs to be achieved, one way or another

Although technology is catching up, creating product passports for every item will not be an easy task, especially as supply chains are already an area needing great improvement. Even though information will be easier to capture at each stage of the process, there still seems to be some questions around the overall accuracy of this data. But as product passports can be connected through blockchain technology, there is an additional layer of trust and security that can be achieved. Unfortunately, even blockchain technologies are still in the process of defining governance and standardisation, putting this kind of technology at the cusp of its potential.

But, in order to have a standardised system, businesses and governments will need to come together to agree upon common standards to be able to scale such a project. New data standards, technological innovations, and supportive policies may be able to bring definition to the global waste crisis, putting fashion players under the microscope. With the continued progress and adoption of solutions such as what Eon Group is offering, the future of fully connected products is not so far out of sight.

What’s in it: circularity!

In the past decade, items that are being sold have not been created with the intent of being durable, repaired, or recycled. This is a major problem as consumers become more conscious about their buying habits, but unfortunately, circular products are not always easy to find. There have even been some activists that want to push the European Union to impose a mandatory European standard for durability and repairability among sold items to ensure that sustainable products are the norm. Although such strict regulation has not proven to be easily enforced, such implications could seriously impact the fashion industry if imposed. Therefore, eco-conscious retailers that want to be ahead of the game should understand how digitalising information through product passports could be a tool for implementing and scaling the circular economy.

The fashion industry is a key piece in the achievement of the circular economy, but without transparency, standardisation, and data sharing, overall progress will be stalled. Digital product passports that can be the holder of all information pertaining to the creation and vitality of goods could unlock a more sustainable economy for all.

Credits: IADS (Mary Jane Shea)

Situation of "luxury" department stores in the world

Situation of "luxury" department stores in the world

What: Coresight reviews the situation for department stores playing in the top tier market, named ‘luxury’ by the research company.

Why it is important: This report provides interesting numbers and a perspective, however is also flawed by a lack of understanding of some aspects of the business, which leads to some confusion in the diagnosis.

Coresight reviews the global situation of “luxury” department stores which are poised to continually reinvent themselves in order to remain relevant to demanding customers. The luxury department stores size is expected to grow +10.7% to $127.5 bn in 2022 and is mentioned in the report as the biggest offline luxury retail channel (61.2% of the total offline sales) which somehow questions the methodology and point of reference. Coresight includes in the Luxury Department Stores cohort the likes of Hyundai, Shinsegae, Takashimaya, Nordstrom, SKP, Golden Eagle, Sogo, Galeries Lafayette, Harrods and others, as shown in the exhibit below.

Coresight identifies 5 key trends for them:

- Reduce the dependence on wholesale distribution, through the development or redeployment of private labels or special partnerships with brands, as well as an increased proportion of concessions granted in stores.

- Increase resale initiatives as illustrated by the Re-store in Galeries, Lafayette, dress rental and fine watches exchange services at Harrods, Reflaunt partnership at Harvey Nichols or a second-hand service at Selfridges or Printemps.

- Achieve renewed relevance as experience centres. Coresight chose to illustrate this fact by mentioning la Samaritaine or the Playhouse at Selfridges, however we believe that SKP-S is the best illustration of this trend.

- Develop popups relationships with DTC brands, in order to bring a new customer in the store,

- Help luxury brands to reach suburban customer, with new store formats able to penetrate new markets and therefore increase the exposure of luxury brands to new communities.

Situation of "luxury" department stores in the world

Reimagining the CHRO role

Reimagining the CHRO role

What: McKinsey polled CHRO across the globe to understand the extent of the role transformation.

Why it is important: The traditional 3 pillar Ulrich model is dissolving as its siloed approach might not be adapted anymore to the current challenges companies face, and their need for flexibility and agility.

The pandemic came with significant challenges, which put the HR role at the centre of the organisation, since it became vital to be able to reorganise teams and processes from scratch in the minimum time possible. While making clear that the position is as central as sales or production, for instance, the pandemic also induced changes which are transforming the HR role.

In the past, HR officers were broadly responsible for 3 areas: being business partners with the rest of the company, provide shared services, and develop centres of excellence. However, this approach (the Ulrich model) could easily lead into siloed organisations and diluting the focus.

According to McKinsey, there are 8 areas of changes when it comes to the role:

- HR should be elevated through digitalization, by automating processes and administrative tasks. It is not about large ERP systems anymore, but solutions, data and employee experience.

- Enabling agility and fluidity, by not organising the HR team anymore according to the 3 pillars, but as pools of professionals who can be quickly deployed to deal with critical issues and priorities.

- Refocus business partners on advising top management rather than working on routine administrative tasks.

- Create HR practice groups to tackle specific and cross-functional HR priorities from end to end, putting an end to the separation between strategic and transactional tasks,

- Organize around employee experience,

- Virtualize centres of excellence and centres of competence, with workflow practice groups, instead of business partners being kept separate from the HQ.

- Put the business in the driver’s seat by shifting responsibility for traditional HR tasks to line managers.

How the wrong KPIs doom digital transformation

How the wrong KPIs doom digital transformation

What: Digital transformation is often seen as an end, when it is a mean. This misconception leads to not making the most of KPIs, which can contribute to the changes in the company.

Why it is important: KPIs can be transformative and MITSloan proposes an approach that contribute to identify, address and improve the reservoirs for growth.

Digital transformation is a mean, not an end. Considering that the digital transformation is a goal can be a source of strategic mistake and can lead to picking up the wrong KPIs, misleading the organisation as a whole. In addition, many legacy companies see KPIs are reporting and accounting mechanisms, and miss their potential contribution to the strategic changes, by helping the decision-making process.

MIT Sloan argues that KPIs should lead, not track, digital initiatives. Top management should define and communicate both the key performance that is required to execute its strategic plan and the digital capabilities that will enable that performance. For instance, dramatically upgrading technology infrastructure only ends in doing the same old things, but in the cloud. This is why the transformation opportunity lies in making strategic metrics both individually and collectively visible and valuable, with a strong Return on KPIs.

For example, a financial services company identified agility (ability to rapidly react and respond to customers’ requests) as a KPI. Legacy systems did not provide any additional value, so the company dissected the processes and identify new measures: session time, autofill, customer effort, loan approvement cycle. This led into generating new questions: for instance, could autofill be used to increase customers’ loyalty by reducing their effort? These new metrics did not just monitor digital agility but informed possible investments for agile improvements. Another example is the Customer Lifetime Value.

MITSloan identifies 4 components of a leadership framework for KPI-driven digital transformation:

- Create a strategic KPI portfolio, with a clear strategic vision, with tangible goals, each of them coming with key inputs and actions, methods for measurements and priority of such measurements. For instance, a global hardware company identified NPS, number of lines of business, number of general ledgers as 3 important KPIs. A financial services company idenfied the ratio of transactional to analytical operations, the percentage of data storage and distribution processes leveraging cloud-based platforms, and the percentage of roles offering flexible work schedules. MITSloan mentions that there is not an ideal number of KPIs, but 5 to 9 are consistent.

- Commit to data as a digital asset. Defining the key data points that individually and collectively make up the KPI portfolio is the first and hardest task. Usually, legacy organisations have bold digital ambitions but inadequate command of their data. This involves strategic investments in making the data more valuable. “Return on data” should be expressed as a necessity at the corporate level and senior directors should be held accountable on this metric.

- Orchestrate data flows to make KPIs shareable, visible and dynamic: usually through a coordination, sequencing and orchestration of the data journey through systems, business units, functions and geographies.

- Commit to continuous KPI improvement: KPIs are waypoints, not endpoints, because digital transformation is a process, not a destination.

Taken together, this framework’s four components enable a virtuous cycle: better data and analytics improve and enhance KPIs, better data orchestration encourages the discover of and access to new data sources, seeing KPIs as dynamically evolving encourages leaders to look for new KPIs to track new kinds of value the company can create, and ongoing improvement and growth is baked in.

Retail-tech landscape: payments

Retail-tech landscape: payments

What: A selection of 40 start-ups involved in payments to provide a wide array of options to retailers.

Why it is important: All department stores know that their POS system is crucial to improve customer loyalty and level of service while also maximizing efficiency. Payment solutions are a key part in this process, all the more that the recent pandemic has changed a lot of mechanisms.

Coresight dedicates a report to the payment solutions currently available on the market, which are increasingly digital due to the recent Covid-19 pandemic. It is expected that the global transaction value with digital payment increases from $7.86 tr in 2022 to $10.7 tr in 2025. The report covers 40 startups and companies spanning across BNPL solutions, checkout experiences, cross-border payment solutions, cryptocurrencies and digital assets, digital wallets, payment gateways and processors, payments-linked loyalty / reward services, risk management and fraud prevention, and subscription management solutions.

In terms of overall directions, they also identify the 2 industry trends:

- Cryptocurrencies are on the rise as their use is favoured by the metaverse expansion,

- The rising inflation across the globe should also favour deferred payment tools

Retail-tech landscape: payments

Fashion retailers race to become ad giants

Fashion retailers race to become ad giants

What: Nordstrom launched its retail media network in the fourth quarter of 2021 and has already seen success driving millions in revenue.

Why it is important: An opportunity has emerged for multi-brand fashion retailers to drive revenue with their own advertising arms. So they are now under pressure to launch their own units. To avoid being shut out of the digital advertising market, they’ll have to move quickly but launching a retail media network requires for them to build out their own technology or partner with existing firms that offer ad tech solutions.

Pressures in the digital advertising space are increasing, due to both rising costs and new data privacy rules that make ad targeting more difficult. Rather than trying to make sense of ever-murkier customer data from Google, Facebook and Amazon, media networks offer retailers the ability to instead grab first-party data themselves. The benefit for brands advertising on retailer platforms — as opposed to more broadly across the internet — is that they are able to get in front of consumers when their intent to shop is higher, that is, on the retailer’s website itself.

While much attention has been paid to the cost of advertising on Facebook and Google, the cost to advertise on a fashion retailer’s advertising platform will likely be subject to the same auction-style dynamics. And just like with social media and other digital platforms like Facebook, Google, and Amazon, fashion retailers will own the data that indicates how effective the marketing is.

The Nordstrom example

Nordstrom, following the lead of not only Amazon but other retailers like Walmart, CVS and Target, became the first major fashion retailer to launch an official in-house media network. This new digital advertising arm allows brands to purchase advertising space on Nordstrom’s owned e-commerce platform, bringing participating brands to the forefront of shoppers’ minds when they’re searching Nordstrom’s site.

Nordstrom’s initial media network offering includes sponsored product ads on its website that appear alongside non-sponsored results, dedicated brand pages and “off-site” options like video, paid social, direct mail and display ads that will appear elsewhere on the internet. Right now, only brands Nordstrom stocks have access to these options, but eventually, Nordstrom plans to make its advertising network available to brands that it doesn’t stock but that customers could be interested in.

For Nordstrom itself, it drove $40 million in revenue in 2021.

There is no such thing as a global shopping mall

There is no such thing as a global shopping mall

What: Unlike entertainment or social media, retail does not break the barrier of going global with a single champion thriving across the planet.

Why it is important: Thriving retailers are the ones who understand their local customers. This is at the heart of all European retailers who know that the Asian tourist bonanza is not going to be back soon. However, it might be a blessing in disguise as they build entry barriers to foreign international champions by doing so.

The New York Times columnist Shira Ovide argues that while technology does not know any boundaries and Facebook, Whatsapp, Google, YouTube or Tiktok are shared global experiences, this is not the case for shopping (online or offline) as there is no global behemoth catering the shopping needs for all customers across the planet.

Even though Amazon announced some years ago that “customers behave the same globally”, this did not translate into a reality: 90% of Amazon’s revenues are made in 4 countries only: the US, Germany, the UK and Japan. Walmart is equally successful in the US, Canada, Mexico and Central America but nowhere else. And the Asian starts (Alibaba in China, Coupang in South Korea) have not done better in terms of expanding internationally. Forrester analyst Sucharita Kodali puts it in these words: “retail is just hard to globalize”. Reasons explored for that state of things are multiple, and hypothetic:

- It could be due to local regulations which are favouring national champions therefore making it difficult for them to enter new markets,

- To thrive on a market, retailers need to acquire a customer knowledge that will not be the same in another country,

- Entry barriers are high in countries where national champions already operate.

The New York Times mentions that not having a global champion may be a blessing in disguise in terms of environmental impact.

Blockchain drives transparency in the supply chain

Blockchain drives transparency in the supply chain

What: Blockchain is already being used in supply chains to create greater visibility and transparency.

Why it is important: Blockchain technology has the opportunity to unlock a lot of information that is typically lost throughout the supply chain. There are many hurdles to overcome, but each successful use case will create more opportunities for growth.

Blockchain initially gained footing in grocery, where knowing the source of a product can be a matter of life or death. The technology is allowing retailers to quickly pinpoint the source of outbreaks of pathogens like E. coli.

But for blockchain to work across the supply chain, everyone involved must add information about products to it, and make that information accessible to everyone else. Not all players are comfortable with sharing information and there are also complications with governance.

As more and more players see success, such as Walmart with groceries and luxury goods with certification, blockchain will be adopted more readily and extended to new use cases.

How to identify the right spans of control for your organisation

How to identify the right spans of control for your organisation

What: McKinsey addresses the notion of organisation complexity through the angle of the maximum span of control, and identifies archetypes to do so.

Why it is important: Instead of using industry norms or other KPIs to make decisions that could become counterproductive, this approach allows to draw a flexible organisation adapted to the tasks to be performed.

Throughout the 20th century, McKinsey has found that there is no single magic number that fits all types of managers and the work that they do, when it comes to the maximum number of people they can manage (Span of Control). Chasing such an idea could actually be counterproductive. They also do not believe that there are industry norms, or corporate size, and propose instead to use managerial archetypes to evaluate the maximum SOC for each of them:

- “Player / Coach”: three to five direct reports (e.g.: Functional vice president)

- “Coach”: six to seven direct reports (e.g.: customer-analytics manager in a marketing group)

- “Supervisor”: eight to ten reports (e.g.: Senior vice president of finance)

- “Facilitator”: eleven to fifteen direct reports (e.g. accounts receivables and payables managers in a large finance organisation)

- “Coordinator”: fifteen or more (e.g. manager in a call centre).

How to identify the right spans of control for your organisation

Retail-tech landscape: E-commerce fulfilment

Retail-tech landscape: E-commerce fulfilment

What: A selection of 45 start-ups specialized in e-commerce fulfilment.

Why it is important: Last-mile deliveries are especially important, as it is on the one hand all about the speed of delivery, but on the other hand the level of service and personalisation.

Coresight reviews a selection of 45 start-ups involved in e-commerce fulfilment across the following categories: micro-fulfilment, order-picking robots, product delivery, returns, sustainable packaging and cross-border e-commerce.

Coresight identifies the 2 following trends when it comes to this part of the business:

- Speed and agility are increasingly vital features for retail operators when it comes to e-commerce. Retailers are using artificial intelligence and machine learning in order to get products into customers’ hands as quickly as possible. For instance, Walmart plans to open a high-tech fulfilment centre in Q2 2022 which will store items to be picked, packed and shipped within one day,

- Cross-border e-commerce will keep its momentum in 2022. 69% of US customers made a cross-border purchase in 2019, and this share increased to 76% in 2021. The most important categories in this part of the business are fashion, beauty and personal care.

The quest for a killer KPI

The quest for a killer KPI

What: The simplification of performance metrics can contribute to the business development, provided the considered metrics are the right ones.

Why it is important: Simplifying and having the right KPI has dramatically positive consequences on organisations and teams, and can be structurally transformative.

Agoda, an Asian-based travel company, discovered that it had too many goals and metrics, creating confusion and waste of energy and resources. It then decided to create a singe key performance indicator in order to unify behaviour between teams and be a shared currency across them.

They share their methodology in this MITSLoan article. This went through a series of A/B testing and test and learn processes on their front-end website, initially with one-off experiments, but soon they centralized learnings into a single unified system, and “experiment engine”. They also understood that the speed of the experiment engine had to be dramatically increased, created a new KPI on speed, and went from a dozen experiments per quarter to more than 1,000. However, this generated bugs, so a KPI constraint was introduced, in terms of code quality.

Soon, they realized that the velocity KPIs was not always focused on the conversion rate itself: teams were rewarded for testing ideas, not for testing ideas with an increased conversion in mind. This is why the primary KPI was replaced by the notion of “incremental bookings per day”. This led to a dramatic increase in terms of productivity, cooperation between teams and will to test new ideas. This also allowed to simplify teams and reduce the hierarchy as a sense of cooperation spread across the company.

MITSloan sums this approach through the following 9 steps methodology:

- At the beginning of each project, define a primary metric of set of metrics that will gauge success,

- Assign a KPI to every project

- Look for a KPI that is relevant across teams, to create a shared language

- Try to break that KPI repeatedly,

- Revise the KPI again and again

- Define a primary constraint that needs to be met while the company strives for the KPI

- Keep the data clean and reliable

- Accelerate innovation and experimentation, but limit errors

- Let the process of measurement inspire the corporate culture.

Shoppers resist price increases

Shoppers resist price increases

What: Retailer efforts to charge more for certain items have met consumer resistance.

Why is it important: With inflation at a 40-year high, companies across the spectrum have been charging more to offset rising costs with little resistance from consumers. That trend is starting to change.

Compared to February 2021, sales are up 17.7%, but a large chunk is due to rising prices. Unit sales of general merchandise goods such as apparel, footwear, toys, and sports equipment declined in nine of the 10 weeks from Dec. 26 through March 5 compared with the same period a year ago, according to market research firm NPD Group.

Around 43% of consumers surveyed by NPD said that if prices continue to rise, they will delay less-important purchases to stick to a budget.

Apparel retailers have been among the biggest beneficiaries of consumer spending as Covid-19 restrictions ease and people refresh their wardrobes in anticipation of more in-person meetings and social events. Chains from Macy’s to Target reported strong holiday sales, and many have reduced promotions and raised prices, a departure for an industry that had been in a deflationary spiral for decades. However, Citigroup Inc. analyst Paul Lejuez noted in a recent report about the impact of inflation on apparel companies, despite a strong job market and rising wages, consumers’ “wallets are not infinite.”

The pushback from consumers varies across categories and brands. Luxury players have been jacking up prices with no visible collapse in demand. Items that are scarce because of supply-chain shortages can also command higher prices. And shoppers are more willing to pay up for fashion items like spring dresses than basic T-shirts.

Analytics company DataWeave Inc. found wide disparities in the price increases by item and gender. The average price of skirts is up 31% compared with a year ago, while pants cost only 8.6% more. Women on average are paying an extra 13% for pants, while men are paying an additional 5.3%.

Retailers are trying to figure out how far to push prices without losing customers and developing workarounds when price increases aren’t feasible. Some brands are reducing costs by using lower-grade leather, lighter-weight cotton, or cheaper trim. Others are switching to less-expensive manufacturing techniques such as single-brushed instead of double-brushed fabrics.

Premium brands are taking the opposite tack, by adding quality to products in the hope that consumers will pay more. When Coach introduced the latest version of its Tabby 26 handbag last spring, which is made of softer, fluffier leather than the original, it raised the price by USD 100. Higher prices can make luxury items seem more desirable. Macy’s has been able to charge more for expensive items but not less-expensive models. The chain raised the price of a $2,000 sectional sofa to $2,200. But it was unable to charge $100 more for a $499 sofa.

NFTs and retail metaverse

NFTs and retail metaverse

What: NFTs are often seen as a significant new technology allowing to protect and very ownership of digital assets. Coresight explores their application in retail.

Why it is important: Even though some might consider it as too early, many brands and retailers have already launched trials with NFTs, often with financial success. Coresight explores their meaning and implication, including in the coming retail in the metaverse activities.

NFTs are non-exchangeable units of data stored on an indelible record of transaction (the blockchain). External events (Covid-19 pandemic) and industry developments (the metaverse being increasingly pushed forward by Silicon Valley) have made NFTs visible to the general public and increasingly popular. According to Coresight, the NFT market represents $35 bn in 2022 and is expected to grow to $80 bn by 2025.

NFTs are central in the metaverse, as users are increasingly interested in equipping their avatars with unique features. The metaverse being in reality a collection of various platforms, NFTs allow for interoperability, allowing users to bring their assets and avatars between virtual worlds. They also allow a very strong individualization per se, as shown by the Ready Player Me initiative, which allowed owners of the CryptoPunks NFTs to have their avatars represented by these NFTs on various virtual word platforms.

Coresight reviews in this report the various technologies available to retailers who want to venture into NFT initiatives, and makes a balance between Solana, Ethereum, Solanart and AtomicMarket.

Notable examples of successful NFT initiatives in retail include Nike, Clinique, or Hot Wheels (toys).

Data is not oil, it is sand

Data is not oil, it is sand

What: An essay on the nature of data, and why the whole conception is misleading (and meaningless).

Why it is important: Success stories as reported in the media can be overwhelming, and lead retailers into making the wrong strategic decisions when it comes to addressing data in the broader view of their digital transformation.

Benedict Evants, a tech columnist and former associate at Andreesen Horowitz, reviews the current ongoing and generalized discussion about data and its ownership. According to him, seeing data as the new oil is a misleading conception, and so is the dream of having a decentralized web architecture where everyone could own and monetize his or her data.

He reminds that data makes sense only at the macro level and that the notion of individual data makes hardly any sense (at least from the capitalistic point of view), let alone its monetization. For him, data is valuable only in the aggregate of millions of grains, this is why for him, data is not oil but sand. In addition, he also reminds that data is a broad word that refers to many different things, contrary to sand where each grain is the same. He gives the example of Instagram data, that would be of no use for an electricity company. Talking about “data” as a generic concept does not have any meaning.

Instead of a collection of discrete units, data should be seen more as an expression of interactions within a network.

Sustainability in sourcing: greening supply chains is more critical now than ever before

Sustainability in sourcing: greening supply chains is more critical now than ever before

What: Coresight explores the challenges retailers could face in improving sustainability in sourcing and how they can resolve them.

Why it is important: As the global pandemic shed light on the weak points in current retail supply chains, they are being revamped. These supply chain make overs should also include making these operations more sustainable.

The Covid pandemic exposed many weaknesses of supply chains and has prompted many companies to restructure various aspects of the supply chain. During this restructuring, companies should consider the tradeoff between costs and sustainability in their new strategies and implement initiatives that produce more environmentally friendly results.

There are many areas of retail supply chain that present opportunities for greening- spanning, pre-production, production packaging, storage, and distribution. Retailers should look to adopt 3D sampling and digital design, implement specific environmental conservation practices for their suppliers, use eco-friendly packaging, implement stricter audits for the use of space in packages, reduce energy use and rethink their sourcing destination mix and transport options.

The challenges of greening supply chains include a lack of visibility into supplier infrastructure and subcontractors, varying sustainability standards between sectors, conflicts between sustainability and procurement strategies, and pressure on supply chains through trade disputes. But collaboration and participation between stakeholders across multiple industries could lead reduce overall impact.

Sustainability in sourcing: greening supply chains is more critical now than ever before

Fixing fashion’s supply chain with company culture

Fixing fashion’s supply chain with company culture

What: The fashion industry has a massive supply chain problem and change begins within a company, starting with C-suite executives and the value system they create.

Why is it important: A persistent lowest-cost mindset over the years created gaps between buyers and suppliers, which deepened amid the global pandemic. The outcome is a trail of imbalances and one-way practices imposed by brands and retailers on supplier networks to cut their own costs and risks, squeezing factories and their workers. The overhang of lost or damaged trust between buyers and suppliers is still with us, a concern that is a major obstacle to a more sustainable future.

Survey results published in a report from BoF Insights, found that 70% of fashion industry executives polled said strengthening supplier relationships was one of the top supply chain priorities.

The Gen-Z consumer crescendo for sustainability has changed everything, there is a generational demand for end-to-end transparency, trust, and accountability, superseding operational language for efficiency alone. Executives must ensure that their business models go beyond seasonal, transactional contracts. The alternative is to be more “relational,” inclusive of end-to-end, mutual incentives for long-term investment.

Over the course of global research and case studies, Harvard production expert and Stanford guru of supply chain metrics, encountered indifference among fashion chief executive officers to primary drivers of market value, such as speed-to-market, order cycles, working capital and forecast accuracy. These were of little interest to merchants insistent on volume, lowest prices and highest incoming margins. The favoured C-suite perspective was demand creation, not supply flexibility.

The short answer to finding a solution is, culture. The internal values of a brand hold the key to a tipping point. Cultural leadership is the prerequisite for meaningful, non-incremental change. Culture matters more than strategy and marketing. It is the basis of a sustainable business model. Fashion must strive for continuous learning, seek and adapt knowledge outside of its industry, and partner in the spirit and reality of value creation with suppliers. Buyers and suppliers, together, create a new equilibrium.

IADS Exclusive - Brand Roundup: Home and Decor

IADS Exclusive - Brand Roundup: Home and Decor

IADS recently held a meeting about on the home and decor sector. Based on market research, the IADS team and NellyRodi presented the most innovative brands from different segments of home and decor: furniture, home appliances, home accessories and electronics. Check out a selection of these brands!

Furniture

Vetsak

Produced locally and sustainably with an innovative design from South Africa. One-of-a-kind, modular, quality, practical furniture, that brings life a little extra comfort.

Check out the Vetsak website here

Lapalma

Balancing craftsmanship, industrial techniques, efficient production, and a focus on details, Lapalma produces and sells its quality design aimed at creating innovative solutions that interact with each other. Lounge, Light Office, Outdoor, Cafè and Home, all customised environments, by extending the range of finishes.

Check out the Lapalma website here

Home Accessories

Ago

Korean design studio specialized in lighting, that searches for a balance between beauty & function with light. With the line between residential and commercial space becoming increasingly blurred, Ago values simple, honest and refined aesthetics.

Check out the AGO website here

Helle Mardahl

Helle Mardahl is an artist and designer with an eccentric and contemporary aesthetic. Playing with forms and materials, she playfully combines strength and fragility, crafting pieces that bring life to spaces. Creating a dreamy universe of richly coloured quirky glass designs.

Check out the Helle mardahl website here

Cookut

Cookut is a brand of kitchen utensils, which also offers accessories for storing and transporting food, as well as hygiene and care products. Their goal is to reduce plastic and daily waste, reduce CO2 emissions while using natural raw materials, promote eco-design and produce responsibly and transparently.

Check out the Cookut website here

The Citizenry

Citizenry believes homes deserve designs with a soul, a story, and a purpose. Country by country, they partner with master artisans, blending modern style with different cultural time-tested techniques. The products reflect a collective of individuals from different cultures and backgrounds who rally together to create something beautiful.

Check out the Citizenry website here

Boy Smells

Highly spirited scented candles, fine fragrance, and intimate wear for all or neither gender. Boy Smells wrap traditionally masculine scents in a prettier bouquet, made with natural oils, all-natural coconut wax, and beeswax blend and are hand-poured in a reusable glass vessel and hand-labeled.

Check out the Boy Smells website here

KJP

Colourful homewares, cheerful print & pattern-focused textiles and lifestyle goods that spark joy.

Check out the KJP website here

Lucas du Tertre

Creating a bridge between India and France and between tradition and modernity. Colourful and printed collections created in the Parisian workshops and printed or woven in India according to ancestral know-how.

Check out the Lucas du Tertre website here

Dusen Dusen

Bold, original prints on versatile, textile and home goods products that includes bedding, throws, pillows, and towels.

Check out the Dusen Dusen website here

Electronics

Mirror

A mirror that is also the ultimate home gym with the most workout variety that actually looks good in your home. 10,000+ classes on demand, 50+ genres, and new live classes daily.

Check out the Mirror website here

Yoto

Carefully connected speakers that puts kids in control of their listening, learning and play. Packed with features for day and night and without any cameras, microphones, or ads.

Check out the Yoto website here

Gomi

Wireless mag chargers, portable chargers and speakers, made out of non-recyclable plastic bags, and powered by 100% repurposed e-bike batteries.

Check out the Gomi Website here

Home Appliances

Netatmo

Aesthetic smart home devices with a variety of products including various security cameras, personal weather sensors, and an internet-connected smoke detector.

Check out the Netatmo website here

Daan Tech

Customisable dish washer with 24 colors to choose from that washes daily dishes for one or two people in just 20 minutes. Bob the dishwasher is the world’s most advanced autonomous and eco-friendly dishwasher thanks to its integrated water tank.

Check out the Daan tech website here

Lema

Lema Air Cleaning System uses nanotechnology and a special UV lamp to generate a photochemical reaction within the wardrobe that naturally destroys viruses, bacteria, odours and mould, improving the customers’ well-being, reducing allergies and respiratory problems. The wardrobe is entirely sanitised, including internally and at the back, without air resistance.

Check out the Lema website here

Somnox

Somnox Sleep Robot is a soft-robotic that enhances the quality of sleep and uses breathing regulation and audio to help fall asleep faster, get deeper sleep, and wake up at the optimal time through a smart alarm.

Check out the Somnox website here

IADS Exclusive: 2021 IADS Academy - Omni-cluster for omnichannel

IADS Exclusive: 2021 IADS Academy - Omni-cluster for omnichannel

In early 2021, the IADS Academy participants were set the task by their CEOs of suggesting ways to develop a truly omnichannel P&L and related KPIs relevant to department stores. Their proposals covered several areas including KPIs and data sharing (see Presentation to CEOs at IADS General Assembly, 28 October 2021; and IADS Academy 2021 report). One of the proposals called for the development of “omni-clusters” of customers. The IADS has attempted to develop this idea.

Imitate or innovate?

In the early days, many omnichannel department stores in effect created a separate and competing business within their companies: e-commerce, which started as an “add-on”, often an experiment, was operated on the same principles as the traditional stores, with the differences that selling took place on a website rather than in physical stores, and that customers were delivered at home instead of carrying their purchases away with them.

As e-commerce began to include more merchandise categories, department stores saw the format as competition, just as they had seen big-box and discount retailers, then fast-fashion companies enter their market and address their customers. It was supposed that by getting involved in e-commerce, the danger could be fended off and those customers tempted by pure online retailers could be brought back to the fold. However, online retail proved to be bigger than expected, customers integrated it quickly into their retail habits and department stores found themselves running to keep up with the trend. Today, it is more of a scramble to adapt to the pandemic new normal. The puzzle of profitability of e-commerce was not solved, even by the pure players.

Integration into the traditional business has been unfortunately very expensive. The original business was not adapted and e-commerce was generally loss-making. Department store companies have had to operate simultaneously two business models: one in which the main cost centres have been real estate and people, as well as the new one requiring significant investment in systems, fulfilment and marketing. In spite of efforts to the contrary, the traditional department stores found themselves competing not only against new online companies but also being cannibalised by their own creation, at first a modest separate pilot but which soon grew into a Frankenstein monster. The admittedly complex model of the traditional department store was clearly inadequate for the job of operating online, and a fortiori inappropriate for an omnichannel retail operation. One consequence is that, under pressure from activist shareholder groups, some US companies have already or are considering spinning off the high growth dot.com part of the business to increase market valuation such as Saks Fifth Avenue and Hudson’s Bay, and also illustrated by the speculations on Macy’s, even if this approach sparks controversies. This suggests that they believe there is no answer to the omnichannel conundrum.

Struggling with channel conflict

Part of the problem has been, of course a shift in customer behaviour and expectations. It is clear that any business model which does not start from the customer is doomed to failure in what has been called “the age of the customer” (from say 2010). Starting from the belief that online customers were different from store customers, department stores operated two separate channels and only slowly came to the realisation that there was such a thing as an “omnichannel customer” (with higher spending than the single channel customer they had been dealing with).

But then the challenge of merging two business models with very different cost structures became apparent. Against the traditional conversion ratios of 40% plus, the online part of the business was confronted with rates as low as 1%-2%; against sales per square metre, online invoked profit per transaction; against shareholder expectations of bottom-line profit, online was operating as a start-up expecting no profit for at least 5 years but demanding rapid growth during that time; against B2B logistics based on store deliveries, online required quick and efficient B2C fulfilment.

As long as the online part of the business represented 5% or less of the total, then it was monitored separately in order to determine its profitability, return on investment and its longer-term future. As time passed, it became clear not only that online was here to stay, but also that it was contributing to store-based business (and vice versa) in a complex and organic way making it almost impossible to isolate online P&L from store-based P&L. (See for example how Macy’s is claiming to “scale omnichannel thinking across the entire customer journey”.)

The question then becomes how to determine the profitability of various parts of the business, how to attribute costs and sales. Furthermore, it has become clear also that the “best” customers are “omnichannel” customers, making full use of all the opportunities available to them across channels to search, gather information, purchase, pay, get delivered and return merchandise. However, it remains unclear to what extent they are the most profitable, as they “consume” expensive services which are implemented through expensive platforms.

Omnichannel means integration

And yet… many department stores are locked into the double P&L model and struggling to determine how to attribute sales and costs. Partly because so many employees are assessed on a series of inappropriate KPIs which actually discourage an omnichannel approach. And partly because data is unavailable to track customers, inventory, fulfilment, returns etc. in sufficiently granular form to allow appropriate attributions.

Integration of channels means first and foremost the integration of data allowing all channels to be under the same control and distribution system. For example, all data on any particular customer must be available in one accessible place whether it concerns purchases or returns in all channels, preferences, hard data as well as unstructured data.

Similarly, inventory data should be updated in real time, any priorities for particular channels need to be clearly set out in order that channel conflict does not develop from limited inventory.

At the same time, traditional KPIs which have been focussed on transactional records are no longer able to evaluate the sometimes complex drivers of customer decisions. It has been suggested that omnichannel KPIs should fall into four main categories: awareness, engagement, conversion, and loyalty. Thus, such KPIs might cover traffic and visits, recommendations and conversion rates, cross-channel conversion and baskets, and advocacy, lifetime customer value, revisit rate and frequency, for example. (See KPI suggestions.)

A new idea: “omni-cluster”

Since the customer journey has become omnichannel, it has arguably become necessary to use management tools and financial statements which reflect this development rather than struggling to attribute revenues and costs to different channels. The notion of “omnicluster” is a proposal in this direction.

Clustering in itself is not a new idea for department stores. Different clusters as applied to department stores include clustering by store capacity (space for example); by attribute (traffic, location, income profiles…); by sales (revenue, inventory turn…); productivity (revenue or gross margin per square metre); price (price profile, elasticity); multi-dimensional clustering; and more.

In the same way, customer clustering is also common. Using algorithms and AI it is generally defined as an improvement on rule-based segmentation since it allows clustering over many more dimensions; allows only small variance within each group; and can be made dynamic and reflecting the current state of data.

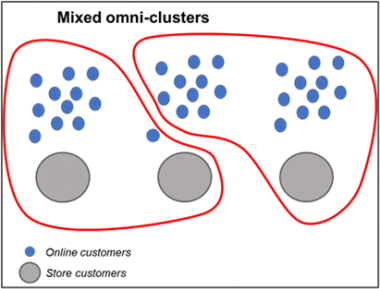

The proposal made by the IADS Academy was to bring the two ideas together to create customer clusters who shopped at stores, online, or both. This would potentially avoid the difficulty of separate or overlapping P&Ls for stores and online. The only rule is that any customer can belong to only one omni-cluster even if they occasionally shop, return, or collect in several physical stores. All revenues, returns and costs associated with a customer would belong to that omni-cluster.

It has been often remarked that not only does online bring customers to stores (and vice versa), but most online customers are more dense around an existing store (while this was a surprising discovery in the early days of omnichannel, it is now fairly obvious since most customers now shop online and stores are situated in the most important markets). In this case, it is clear that an omni-cluster may consist of one or more stores and the online customers residing around that store. This is the simple omni-cluster model as favoured by Magasin du Nord for example.

If, however, a number of online or omni customers have a preference for direct contact with a distant store (say a flagship store, or a store closer to their office rather than their residence), then one mixed omni-cluster might include a store, its geographically close online customers as well as online customers geographically closer to a different store. This may happen also if the stores are clustered by size as they are at Manor, for example.

If store customers are very mixed (tourists and locals, for example), then one can imagine an omni-cluster made up of local store customers plus online, and another partial omni-cluster made up of tourists and the much smaller online tourist customers. A business which involves franchised stores might include its own stores and all online customers in its omni-clusters but not include the franchised stores. These cases may be more appropriate at, say, Galeries Lafayette.

A series of ecosystems

As these examples show, the criteria for omni-cluster membership may obviously vary from one company to another according to its history, its organisation, its market etc. It is a flexible model. The definition criteria of omni-cluster will be a function of the particular circumstances of each company and its history as well as of the omnichannel strategy pursued by a company (aggressive online growth, new store openings or potential store closures etc.).

The aim is primarily to group revenues and costs into a number of omnichannel P&Ls which cover total operations of a cluster which can serve to manage operations (through the related KPIs), and which can be consolidated into a total business P&L. While the different omni-clusters can be compared, it is clear that none will be exactly comparable to any other. For example, geographical location or the number of stores in a cluster may have an impact on fulfilment costs.

However, the advantage of this model is that it highlights the profitability of the customers in any one cluster (for example how much they spend in all channels, frequency, rates of return, margin per customer etc.). Clearly the costs of store personnel also do not relate only to store customers, which distorts store-only P&Ls. Potentially it also allows the evaluation of the true loss of revenue through a store closure.

The kind of integration referred to above moves closer to an “ecosystem” perspective of the retail business. Indeed, a degree of “unbundling” will be necessary to evaluate the costs attributable to an omni-cluster. When that exercise is pursued, then it becomes possible to find potentially more appropriate, more efficient or more effective solutions before rebundling these into an omni-cluster ecosystem.

Warnings, dangers and the way forward

However, such a move would make it quasi-impossible to spin off the dot.com part of the business as has been done recently by HBC with Saks Fifth Avenue and Saks.com. There are currently some reports of Macy’s considering a similar move. It is clear, however, that these examples are financially motivated and a result of pressure from activist shareholders. They are also more appropriate to larger companies. A smaller omnichannel department store following the integrated omnichannel route will be capitalising on its unique status as what Bain has called a “regional gem”. Once established, an ecosystem can no longer be dismantled and split up into its original component parts. It competes as a whole, not as a multi-channel entity. However, this commitment is no more risky than the spin-off of the dot.com part of the business may turn out to be for larger companies which choose this way.

The omnichannel route might also imply considerable reorganisation of the traditional bricks and mortar assets as illustrated by the John Lewis case which is closing and shrinking so many of the stores it (perhaps unwisely) opened while it was expanding its online business (now around 60% of total revenue). It also sold its Ocado stake in 2010 for £250m which would be worth nearly £2bn today. Rather than spin off the online business, it is reshaping the total business under a new team, focusing on own brands, convenience, high productivity, sustainability, and the integration of formats.

John Lewis raises the question of how to implement the shift towards real omnichannel in today’s retail landscape. Clustering, new KPIs and rejigged P&Ls cannot be put in place in a day. The question therefore is: What would a transition phase towards omni-cluster P&L look like? Who should guide the transition, and how can investors be won over to support this longer-term shift?

Credits: IADS (Dr. Christopher Knee)

Transformation in retail: Innovative Thinking Interview with Chafik Gasmi , Chafik Studio

Transformation in retail: Innovative Thinking Interview with Chafik Gasmi , Chafik Studio

*2020-2021 has been more than a period of pandemic and crisis: by its magnitude and lack of precedence, it has literally changed the world, especially the retail world, by changing habits: digitalisation and new purchasing habits, work from home and the question of commuting, notion of essential vs. non-essential goods.

The IADS launched a series of interviews with innovative thinkers to understand their views on how to deal with such changes. All organisations have proved their resilience and ability to cope with the emergency of the situation, however, it is a very human thing to tend to come back to habits whenever possible. What happened? How can we make the most of what we learnt and how can we make sure our organisations and thinking processes are durably impacted?*

Introduction: Chafik Gasmi, founder of Chafik Studio

For this session, we welcomed Chafik Gasmi, based in Paris and founder of architectural company Chafik Studio.

Chafik Gasmi, 59, launched his first designer’s furniture line in 1990, just after graduating from the Ecole d’Achitecture de Paris. This line was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Salon du Meuble in 1992. Following this initial success, his projects were selected by the French State to furnish the Prime Minister offices.

In 1996, the founder of Sephora, Dominique Mandonnaud, asked Chafik Gasmi to design the Sephora flagship boutique in Champs Elysées, to help him bring his vision alive. This was Chafik Gasmi’s first venture in cosmetics, and ended up in a mix of architecture, design, cosmetics, with a true customer-oriented vision. Then, after LVMH acquired Sephora in 1997, Gasmi was appointed as the artistic director for Sephora and personal advisor of Mr Arnault for several brands on branding and retail experience, including Kenzo, Guerlain or Dior. After a stint as Artistic Director at Baccarat, he created Chafik Studio in 2004. In 2010, he initiated a long-term relationship with Lancôme as well as with Fendi Casa.

Nowadays, Chafik Studio is a multidisciplinary structure, with competencies ranging from architecture, interior design, product design, retail design and artistic direction. The company is involved in hotels, department stores, retail spaces, furniture and objects, and is able to work with both corporate companies and family businesses.

Part 1 – Dealing with innovation

*IADS - Chafik, your studio is renowned for its groundbreaking approach, yet always keeping in mind the needs of customers, which explains why you have developed so many retail concepts with the biggest brands. How do you foster this creativity on a daily basis?*

Chafik Gasmi - First of all, the most important, and this is common to both family businesses and corporate companies, I always deal with the person who ultimately pays for the project, not intermediaries, even if they hold top positions. Innovation is always very difficult and can generate anxiety. For me, it is easier to talk about changing rules with the guy who pays, rather than how to deal with the rules with the guy who executes.

When it comes to my method, I always look at things in a very fresh, almost childlike way. In other words, we force ourselves to be naïve, curious, and ask questions, to make sure we see things differently, challenge the status quo, and get excited in the way. The idea is not to be different for the sake of it, but to generate a tension based on trust, within a reassuring framework.

Innovation can generate anxiety and trust is key to taming the feeling of danger.

*IADS - How do you manage creativity within your organisation? How are ideas generated and with what process? Also, how do you onboard newcomers in your organisation and make sure they fit with your mindset?*

CG - First of all, I avoid creating a silo between my team and my customers. We design the brief together, because the answer is often in the question. If you do not take part in the question elaboration, you will miss something in the answer.

Then, once the brief is done, we do the first meeting with our clients in our studio. During this “project session”, we work together on rewording the brief and gathering the ideas. Everyone sketches their ideas, which at the end I personally synthesise. The goal is to reach a very strong, clear and simple idea, coming from a series of interactions between everyone, including words, sketches, feelings.

Once the idea is here and we are ready to launch the project, we gather all the people who will be involved at one stage or another (contractors, third parties, middle management…) in a room to explain the project. During that moment, we identify in advance all the blocking elements and kill negative thinking. It is all about resolving all opposition at the launch instead of fine-tuning along the development phase, to keep the project strong and fresh. Any other approach invariably ends in concessions and compromises, which always dilutes ideas.

Given the level of interaction with which we work, I must say that Covid-19 has been a difficult period as we lost a lot of the intuitions we usually get from interactions. Video conferencing helps in the thinking process, but not on the perception of feelings. This is why we took a step aside and seized the opportunity to think about our own processes, organisation… to be ready for better days in terms of operations. Covid-19 has been quite difficult for creativity itself I must admit.

Part 2– Retail

*IADS – Coming back on your statement that “answers are usually in the question”, what was the answer in the 1996 Sephora store question, and are these answers still valid for 2022? What would you change if you had to do this project again?*